Die Bell 429 von ROBAN/Scaleflying.de

Bericht:

Wie es dazu kam

Hier geht es um mein Exemplar der ROBAN Bell 429 und wie es mir damit ergangen ist. Vielleicht hilft das jemandem, so wie es mir immer hilft, Berichte anderer Modellflieger zu lesen.

Einige allgemeine Informationen zu diesem Modell gibt es hier auch, einiges ist im Internet zu finden (siehe "Weiteres"), aber das meiste ist das, was ich gerne gelesen hätte, bevor ich diesen Hubschrauber zusammengebaut habe – zusätzlich zu der dennoch wichtigen Anleitung von ROBAN.

Manches trifft sicher auch auf die anderen Modelle aus der "SuperScale"-Reihe von ROBAN zu. Sie sind alle ähnlich aufgebaut und enthalten die gleiche 800er Mechanik.

Nachdem ich 2020 mit meiner HIROBO Schweizer 300 sechs schöne Flugstunden angesammelt hatte, wir aber im nächsten Corona-Lockdown saßen, wollte ich einen noch größeren Modellhubschrauber haben – wahrscheinlich aus reiner Gier. Er sollte mindestens vier Blätter am Hauptrotor haben und wieder "scale" sein, also nicht für Kunstflug – sozusagen altersgerecht (mittlerweile noch wichtiger).

Eine Hughes 500 hätte mir immer noch gut gefallen, aber ihr Rumpf ist im Verhältnis zum Hauptrotor noch größer als bei der Schweizer 300. Das sähe nicht nur massig aus, sondern würde – mit dem besonders hohen Landegestell – sehr hoch werden. Dann hätte ich wohl Probleme beim Verladen ins Auto (dachte ich zumindest damals, aber das war falsch).

Etwas "schlankeres" musste es also sein – wie die Bell 429. Die von Air Zermatt kannte ich von Fernsehen und YouTube und sie gefiel mir ausnehmend gut (und offenbar nicht nur mir, sondern vielen). Ein Vereinskollege, der den 700er Tiger von ROBAN/Scaleflying.de besitzt, brachte mich dann auf das Modell. Er hat mir dringend zugeraten, nicht die 600er, sondern die 700er B 429 zu nehmen (und hätte mir zu einer 800er geraten, wenn es die gegeben hätte).

Als das Paket dann so bei mir auf dem Teppich lag, bekam ich doch einen Schrecken, was ich mich da getraut hatte. Aber wenn der Heli erst einmal gebaut ist, würde ich mich wohl an seine Größe gewöhnt haben. Außerdem sieht er auf dem Flugplatz nicht mehr so mächtig aus, wie ich von dem 700er Tiger und einem 800er Airwolf weiß – und größer fliegt schöner, da hatte ich keine Sorge.

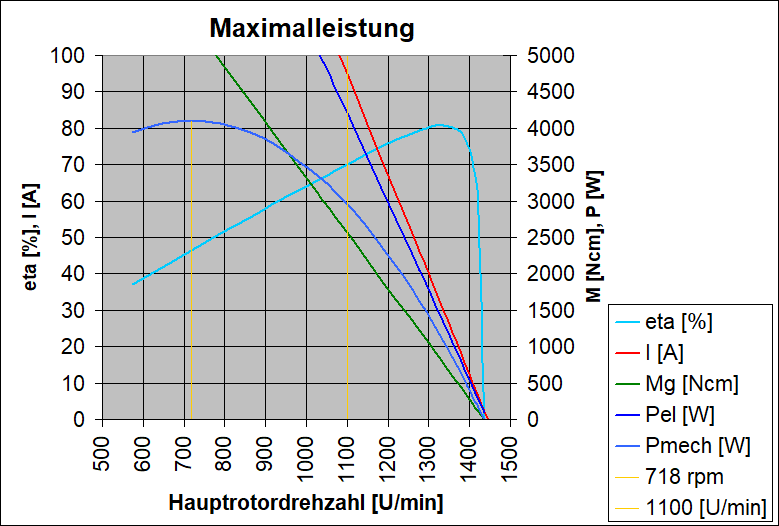

Die Größe ist also als 700 angegeben, wobei die neuen Rotorblätter 720 mm lang sind – gibt 1,60 m Rotordurchmesser (1,56 m laut Anleitung). Die Mechanik wird als 800er bezeichnet, weil sie für diese Größe gemacht ist (und dies ist ein 4-Blatt-Rotor), und ein 750er Motor mit 450 kv wird in der Anleitung genannt. Ein 700er Motor (natürlich mit 12s LiPo-Akku) passt allerdings mit seinem Durchmesser gerade gut hinein und reicht laut Scaleflying.de auch gut aus (dies ist ein Scale-Heli), ebenso wie die von Scaleflying.de empfohlene Rotordrehzahl von 1100 U/min. Das Gewicht ist mit 8 oder 9 kg angegeben, je nachdem wo man nachliest. Wie zu vermuten war, stellte sich 9 kg als realistisch heraus und 8 kg als absolute Untergrenze. Die Maßangaben in der Anleitung stimmen, der Maßstab ist 1:7 – etwas kleiner als bei der HIROBO Schweizer 300 (1:6,32).

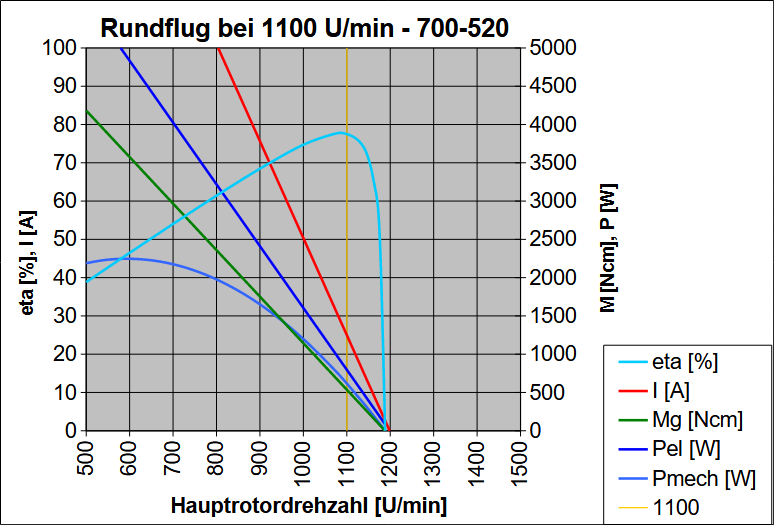

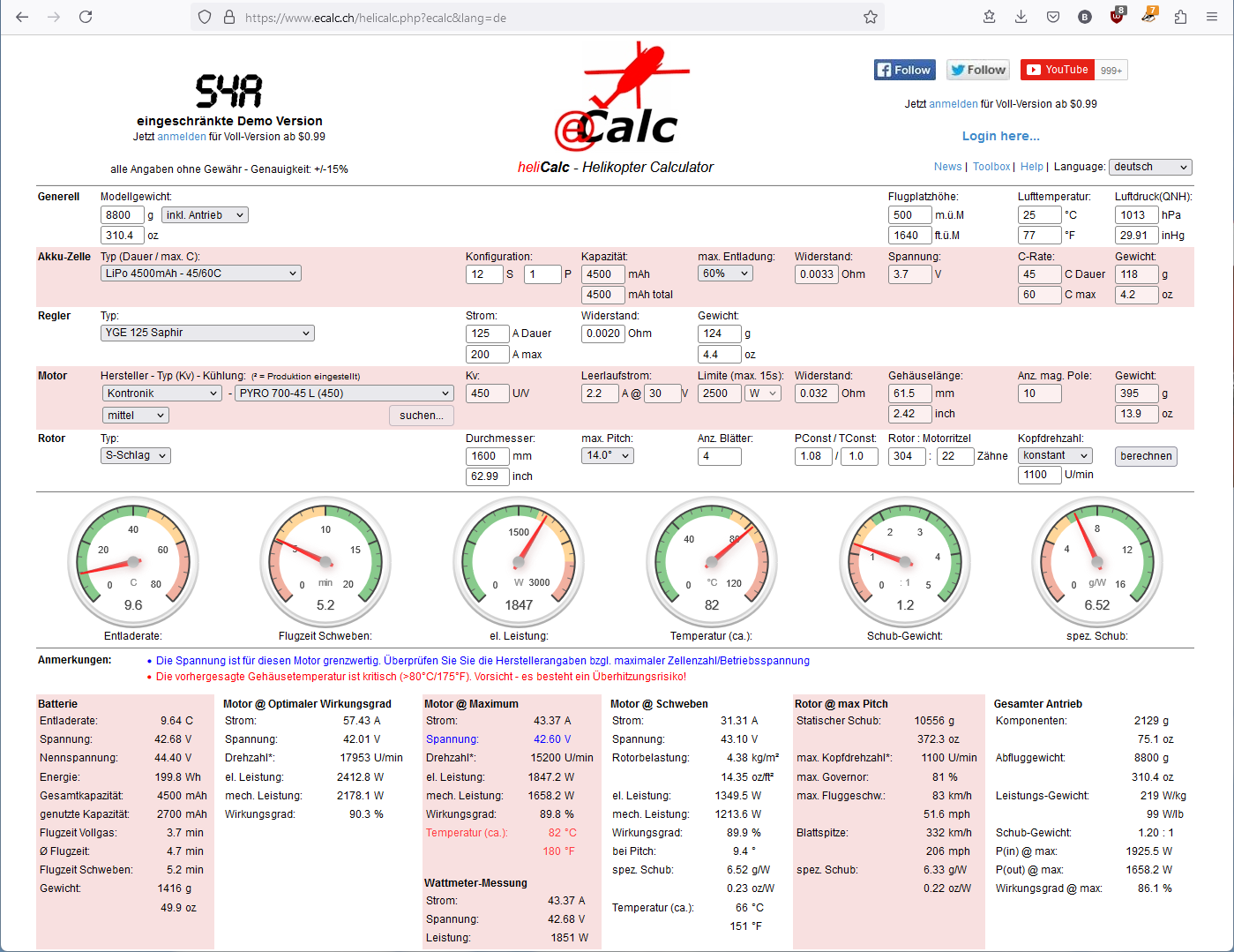

Auf YouTube habe ich ungefähr 40 Videos von der ROBAN Bell 429 gefunden (siehe "Weiteres"). Wenn dort der Antrieb erwähnt wird, dann ist es meist ein größerer Motor (750 oder sogar 800) mit höherem kv und eine höhere Rotordrehzahl. Das kam mir etwas übertrieben vor und ich vertraute eher den Empfehlungen von Scaleflying.de, die mir sogar auf Anfrage per E-Mail noch einmal bestätigt wurden (danke!). Um aus Vertrauen Gewissheit zu machen, wurden Antrieb (siehe unten) und Rotoren des Modells im Flugsimulator abgebildet (siehe unten) – und ja, die Angaben sind richtig.

Was mir etwas Sorgen machte war meine Unerfahrenheit. Zwar weiß ich, wie alles funktioniert, aber ich habe keine praktische Erfahrung. Die HIROBO Schweizer 300 war eine gute Übung, aber da war alles perfekt vorbereitet und beschrieben. Die Anleitung zur B 429 hatte ich vor dem Kauf schon von der entsprechenden Webseite von Scaleflying.de heruntergeladen. Sie kam mir recht kurz und etwas verwirrend vor und das bestätigte sich, als der Heli geliefert war. Drei zusätzliche Zettel enthielten wichtige Informationen, die in der Anleitung (Version 2.0 – Mai 2016) noch nicht enthalten sind, aber das war es auch.

Auf dem YouTube-Kanal von Scaleflying.de gab es vier nützliche Videos, in denen die Montage einer 800er-Mechanik gezeigt wurde. Besonders wurde darauf hingewiesen, daß die Mechanik vormontiert ist, aber komplett zerlegt und dann mit Sicherungsmittel wieder zusammengebaut werden soll. Außerdem soll das Zahnflankenspiel der Kegelradgetriebe zum Heckrotor geprüft und gegebenenfalls mit (im Bausatz enthaltenen) Unterlegscheiben eingestellt werden (und in dieser neueren Version auch das Spiel des Schrägkugellagers an der Hauptrotorwelle).

Was mich gleich irritierte war der Hinweis, daß Schrauben mit Wärme gelöst werden müssen, wenn sie durch Sicherungsmittel zu fest sitzen. Mein Vereinskollege meinte, die Vormontage spart die Verpackung der vielen Einzelteile und die genaue Beschreibung ihrer Montage. Das leuchtete mir ein, aber warum war dann schon Sicherungsmittel verwendet und – wie sich später herausstellte – die Winkelgetriebe (wie auch das Schrägkugellager) schon mit Unterlegscheiben eingestellt und gefettet? Für mich sah es eher nach Haftungsausschluß des Vertreibers Scaleflying.de aus (der damals sogar Anteile an ROBAN hielt) und das hat mich zunächst sehr gebremst.

Im Rückblick ist diese Angelegenheit sogar noch zweifelhafter. Ich hatte die deutsche Anleitung durchgearbeitet, die ich von Scaleflying.de heruntergeladen hatte und die (auf Papier) auch dem Baukasten beilag. Erst später habe ich die originale englische Anleitung heruntergeladen und fand dort (auf Seite 4) die Sätze "Factory pre-assembled components have been assembled with all the required thread lock and lubricants, and have passed quality control. It is not necessary to disassemble and re-assemble them." (Ab Werk vormontierte Baugruppen wurden mit aller nötigen Schraubensicherung und Schmierung montiert und sind qualitätsgeprüft. Es ist nicht nötig, sie auseinanderzunehmen und wieder zusammenzusetzen.) Vermutlich hatte Scaleflying.de die Anleitung ins Deutsche übersetzt und absichtlich diese beiden Sätze ausgelassen (und den Raum leer gelassen). Im Video betonte Herr Illig, daß man die ganze Mechanik auseinandernehmen und mit Schraubensicherung wieder zusammensetzen sollte. Es ist nicht klar, was genau jeweils von ROBAN und Scaleflying.de gemeint war, und wahrscheinlich liegt die Wahrheit irgendwo in der Mitte.

Zusammenbau

Der Hubschrauber ist günstig für das, was er bietet, aber er kostet trotzdem eine Menge Geld. Deshalb wurde er zum Weihnachtsgeschenk erklärt und zunächst nicht ausgepackt. Die verbleibende Zeit wurde genutzt, um die nötigen (und insgesamt noch ein Viertel mehr als der Bausatz kostenden) Komponenten zu beschaffen: Motor, Regler (noch ohne Kondensatoren) mit USB-Adapter, Sicherheitsschalter für Antriebsakku (noch ohne Widerstand) mit Empfängeradapter, vier Servos, Kreiselsystem ("flybarless"), Empfänger, Telemetrie (GPS, zwei Spannungssensoren, Aufzeichnungsgerät), Schalter/Mischer für zwei Empfängerakkus, Kabel und Stecker – aber noch keine Akkus. Am ersten Weihnachtstag wurde dann ausgepackt und als erstes die Mechanik untersucht.

Mechanik

Von rechts: Mechanik, eingeschweißt die Teile des Motorwellen-Stützlagers, Hauptrotorkopf, Heckrotor mit Winkelgetriebe, Heckrohr mit Heckwelle verpackt, Haupt- und Heckrotorblätter – wunderbar!

Besonders gefiel mir, daß ich die neueste Version bekommen habe, in der noch einiges verbessert wurde: Stützlager für die Motorwelle, schrägverzahntes Hauptgetriebe, Schrägkugellager für die Hauptrotorwelle, längere Hebel für die Taumelscheibe, dadurch längere Hebelarme an den Servos, Blattanlenkungen ohne Taumelscheibenmitnehmer, längere Rotorblätter, Hauptrotorblätter mit S-Schlag-Profil.

Das sollte ich also alles auseinandernehmen? Die Freude wich Ärger. Deshalb habe ich mich oft gar nicht mit dem Heli befassen wollen. In Zeiten, in denen ich gelassener war, habe ich die Videos von Scaleflying.de angeschaut, über die Montage von Getrieben gelesen und immer wieder Mechanik und Rotorköpfe untersucht.

Zwischen diesem Bild und dem nächsten liegen schließlich neun Monate. Im Sommer ging es dann aber ganz schnell. Die Rotorköpfe wurden kontrolliert und erwiesen sich als fest (mit Sicherungsmittel) verschraubt, während die Schrauben an den Carbon-Seitenteilen kein Sicherungsmittel hatten. Die Mechanik wurde teilweise demontiert, um das Winkelgetriebe umzubauen, dann mit Sicherungsmittel wieder zusammengebaut.

Das Ergebnis gefällt mir sehr gut, auch wenn ich immer noch unsicher bin – wegen der Schraubensicherung, des Getriebespiels, des Lagerspiels. Das Heckrohr liegt wirklich etwas schräg; so läuft es dann in der Hecktüte, wenn die Kabine des Helis waagerecht liegt (im Vorwärtsflug). Der Rotormast ist dann um den gleichen Winkel nach vorne gekippt (weniger als beim Original, wo der Rotormast schon am Boden um 5° nach vorne gekippt ist). Die 800er-Mechanik (genannt SM2.0 Mechanics) von ROBAN ist im Prinzip immer gleich, das heißt in deren SuperScale-Modellen, aber die Carbon-Seitenteile sind für jedes Modell anders (und einige Wellen auch). Bei der B 429 liegt eben das Heckrohr bezogen auf die Kabine etwas schräg und relativ hoch. Hier gibt es auch kein 45°-Winkelgetriebe im Heckrohr wie beim Tiger.

Übrigens sind die drei Halter für die Heckrotoranlenkung nicht nur einfach aufgeschoben. Scaleflying.de gab den Hinweis, daß man dann noch einen Kabelbinder zwischen dem Ring des Halters und dem Rohr durchziehen kann. Man zieht, bis er mit seinem Verschluß an einer Seite an den Ring stößt, und schneidet den langen Überstand an der anderen Seite ab. Nun ist der Halter geklemmt und rutscht und dreht nicht.

Die beiden Abstrebungen des Heckrohrs sind aus Carbon, die Beschläge aus Aluminium. In einem der Videos von Scaleflying.de wurde erwähnt, daß sie bei jedem Modell anders angebracht werden und man an Unterlegscheiben die vorgesehenen Schrauben an den Seitenteilen erkennt. So war es auch und das Ganze passt so durch die Öffnung hinten im Rumpf, also wird es wohl stimmen.

Der Motor treibt einen Zahnriemen, den man seitlich aus dem Rahmen hervorkommen sieht. Über der großen Zahnriemenscheibe sitzt ein stählernes Ritzel, welches das hier sichtbare weiße Kunststoffzahnrad (Großrad) und damit die Hauptrotorwelle antreibt.

Die drei Taumelscheibenservos sind jeweils mit einem 90°-Umlenkhebel in klassischer 120°-Anordnung angelenkt. In dieser neuen Ausführung sind die drei Umlenkhebel länger als früher und die drei Schubstangen zum Servo alle gleich lang.

Der KONTRONIK Pyro 700-45 (kv 450) wurde wegen der guten Erfahrungen mit dem Pyro 600-09 (kv 930) in meiner HIROBO Schweizer 300 gewählt. Mit ungefähr halb so großem kv ist er für 12s statt 6s LiPo vorgesehen.

Ein stärkerer Motor ist laut Scaleflying.de nicht nötig (finde ich jetzt auch, siehe unten). Wenn ich einen solchen denn wollte, dürfte er aber keinen wesentlich größeren Durchmesser (als diese 51 mm) haben, damit er noch in die Ausbuchtung des Rahmens passt.

Man muß sich bei der Montage des Motors entscheiden, ob die sehr steifen Anschlußdrähte (nicht -kabel) schräg nach vorne links oder rechts zeigen sollen. Das hängt davon ab, wie der Regler davor angebracht werden soll (siehe unten).

Der Motor sitzt auf einer Art Schlitten, der mit zwei Schrauben nach vorne (links in den Bildern) gezogen wird, um den Zahnriemen der ersten Getriebestufe zu spannen.

Hier sieht man die beiden Spannschrauben und das Zahnriemengetriebe. Wenn der Zahnriemen richtig gespannt ist, werden die vier Schrauben in den Motor festgezogen. Ich habe blanke Schrauben und Unterlegscheiben verwendet (hier gut zu unterscheiden), während (recht kurze) schwarze dem Bausatz beilagen.

Das T-förmige Stück ist das Stützlager für die Motorwelle. Es hat drei "Füße", die mit drei der Schrauben, die Motor und Spannschlitten klemmen, mitgeklemmt werden – eine "Fummelei", aber machbar. Ich hoffe nur, daß ich beim Anziehen der Schrauben keine Verspannung der Welle hervorgerufen habe.

Nur dann verhindert das Stützlager dauernde Kraglast auf der Motorwelle und ist deshalb eine sehr gute Sache. Man muß aber auch die Ausführung des Motors mit dem längsten Wellenstummel nehmen – hier 38,5 mm (6 mm Durchmesser) – und das Riemenritzel mit den Madenschrauben zum Motor hin einbauen – nicht wie in der Anleitung zuerst gezeigt, sondern wie speziell für das Stützlager gezeigt und wie im Video.

Übrigens hatte ich gehofft, daß sich der Zahnriemen zwischen den beiden Seitenscheiben des Ritzels auf der Motorwelle zentrieren würde. Beim Probelauf zeigte sich aber, daß er der Schwerkraft folgt und gegen die untere Scheibe läuft. Ich musste das Ritzel noch einmal lösen und einen Millimeter weiter nach oben (zum Motor hin) versetzen, damit der Zahnriemen im Betrieb mittig auf dem großen Abtriebsrad läuft. Das halte ich für wichtig, denn wenn der Zahnriemen auf dem Rand des Abtriebsrades laufen würde, wäre er in kurzer Zeit zerstört. Man braucht einen Inbusschlüssel mit Kugelkopf, der schräg angesetzt werden kann, und muß darauf achten, die recht kurzen Madenschrauben gerade (nicht verkantet) in das Gewinde zu drehen.

Die Zähnezahlen des Zahnriemengetriebes sind 22 und 78 – Untersetzung 3,55:1. Dann folgt die zweite Getriebestufe mit schrägverzahntem Stahlritzel und Kunststoffrad – Zähnezahlen 20 und 78, Untersetzung 3,9:1. Die Untersetzung vom Motor zum Hauptrotor beträgt folglich 13,83:1. Setzt man die empfohlene Hauptrotordrehzahl von 1.100 U/min voraus, dann muß der Motor mit 15.210 U/min laufen – kein Problem bei 30.000 U/min Maximaldrehzahl (und 12s LiPo).

Unter dem großen Zahnriemenrad sitzt ein Kunststoffzahnrad des Heckrotorgetriebes. Das zweite Zahnrad dahinter treibt die senkrechte Welle zum Winkelgetriebe darunter an. Letzteres ist, wie das Winkelgetriebe am Heckrotor, 1:1 untersetzt.

Die Zähnezahlen des Stirnradgetriebes sind 40 und 32, also ist die Übersetzung 1:1,25. Mit der Untersetzung 3,55:1 der ersten Getriebestufe beträgt die Untersetzung vom Motor zum Heckrotor dann 2,84:1. Bei 1.100 U/min Hauptrotordrehzahl läuft der Heckrotor mit 5.363 U/min (1:4,9). Mit seinen 290 mm Durchmesser (280 mm laut Anleitung) und vier Blättern dürfte er also einige Kraft haben (und der Simulator bestätigte das schon).

Das Winkelgetriebe wurde "umgedreht", das heißt das Zahnrad auf der senkrechten Welle wurde von oben nach unten versetzt, um den Drehsinn umzukehren. Jetzt dreht der Heckrotor richtig herum, nach Vorbild und wie es "aerodynamisch" sein soll.

Dieses Winkelgetriebe macht mir immer noch Sorgen, obwohl alles richtig aussieht und funktioniert. Es war auch ein Anleitungsblatt beigelegt, auf dem besonders auf das wichtige Einstellen des Getriebes hingewiesen wird, und dort ist es so wie hier abgebildet. Wahrscheinlich zeigt das Bild aber das Getriebe eines anderen Hubschraubermodells, vielleicht mit rechtsdrehendem Hauptrotor. Jedenfalls war die Abflachung der Welle für die Madenschraube des Kegelrades nicht symmetrisch und musste (mit Schleifscheibe in Dremel) verlängert werden. Der "falsche" Drehsinn des Heckrotors war also sozusagen ernst gemeint. Meine kurze E-Mail-Anfrage bei Scaleflying.de, ob es einen besonderen Grund dafür gibt und ob es Gründe gegen den Umbau gibt, wurde einfach nicht beantwortet. Mein einziger Anhaltspunkt war eine Explosionszeichnung:

Sie zeigt die Bestandteile (Ersatzteile?) des Getriebes sehr gut und in der Lage, in die ich sie jetzt gebracht habe. Die Anmerkung darunter lautet auf Deutsch: "Um die richtige Drehung und Funktionsweise des Heckrotors zu erreichen, kann es nötig sein, das Antriebszahnrad und die Abstandshülse umzudrehen." Aber bedeutet das auch, was ich darunter verstehe? Wie auch immer…

Den Umbau des Getriebes habe ich genutzt, um mir alle Details anzuschauen. Dazu habe ich das ganze Getriebe aus dem Rahmen ausgebaut, was recht aufwendig war. Es geht auch einfacher, wenn man die untere Lagerplatte abschraubt und das Stirnrad oben sowie das Kegelrad löst. Dann kann man die senkrechte Welle aus den Zahnrädern und der Messing-Distanzhülse nach unten herausziehen. Vorher war also das Kegelrad oben und die Hülse unten. Das wurde umgedreht und alles passte wie vorher.

Über dem Zahnrad lagen zwei Distanzscheiben, um das Getriebe einzustellen. Die Scheiben wurden natürlich jetzt unter das Zahnrad gelegt. Nach meiner Meinung war das Getriebe damit schon richtig eingestellt; man darf sich nur nicht darauf verlassen, weil Scaleflying.de nicht haften würde. Das ist keine theoretische Frage, denn mein Vereinskollege hat seinen Tiger zweimal durch Absturz verloren, weil das 45°-Winkelgetriebe zum Heckrotor versagt hat. Es war natürlich seine Schuld, das heißt er hat nichts ersetzt bekommen. (Jetzt überlegt er, ob er statt dessen eine biegsame Welle einbaut oder das neue Getriebe von ROBAN, das viel besser zu sein scheint.)

Aus drei Gründen glaube (oder hoffe) ich, daß meine B 429 nicht wegen Getriebeschadens abstürzen wird: (1) Die 90°-Winkelgetriebe sind offenbar nicht anfällig oder kritisch, denn Helikopter Baumann bietet 45°-Getriebe mit drei 90°-Zahnrädern an – hier. (2) Bei der Untersuchung des Getriebes wurde mir klar, daß beide Kegelräder so einzustellen sind, daß die Zähne nicht versetzt zueinander stehen. (Bei den schadhaften 45°-Getrieben sind die Zähne ganz kleingeschliffen, aber bei einem der beiden Räder außen nicht.) Wenn das schon nicht stimmt, lässt sich auch das Zahnflankenspiel nicht richtig einstellen. (3) Die 90°-Winkelgetriebe haben ein starres, offenes Gehäuse, so daß die richtige Einstellung sichtbar ist. Die 45°-Getriebe haben ein etwas weiches, geteiltes geschlossenes Gehäuse, so daß die letztliche Einstellung nicht sichtbar und vielleicht eine richtige Einstellung nicht einmal wahrscheinlich ist.

ROBAN müsste es wirklich wie HIROBO machen: auf jeden Fall ein solches Getriebe wie das 45°-Getriebe fertig montiert und eingestellt liefern. Sie könnten es vielleicht so konstruieren, daß keine Einstellung nötig ist, oder zumindest eine Vorrichtung bauen, mit der die Einstellung leicht und sicher gelingt – aber im Werk. Sie müssten die Verantwortung, das heißt Haftung übernehmen, aber das bekommen sie wohl nicht hin.

Allerdings weiß ich nun immer noch nicht, wie ich einstellen soll, und kann nur raten. Im Video zeigte Herr Illig von Scaleflying.de ganz gut, wie man den Zahnriemen richtig spannt. Aber in dem Winkelgetriebe stocherte er nur mit einem Schraubenzieher herum (geht auch nicht anders, es ist ja nichts zu sehen) und sagte dazu, daß man das Spiel richtig einstellen muß – aber nicht wie. Nach meiner Meinung war das Winkelgetriebe richtig eingestellt, das heißt ich könnte es nicht besser machen.

Das galt auch für das Getriebe hinten am Heckrohr. Es ist aus den gleichen Teilen aufgebaut wie das Winkelgetriebe vorn, nur sind die Lagerplatten näher beieinander. Man kann leicht sehen, daß beide Kegelräder richtig zueinander stehen. Und durch Bewegen der Wellen kann man spüren, daß kaum Spiel zwischen den Zahnflanken ist. Gefettet waren die Kegelräder auch schon.

Der Heckrotor wurde auf den umgekehrten Drehsinn umgebaut: die Anlenkhebel von den Kugelköpfen abgezogen; die Blatthalter umgedreht, so daß die Anlenkung "voreilt"; die Kugelköpfe herausgedreht und umgekehrt wieder eingeschraubt (natürlich mit Sicherungsmittel); die Anlenkhebel wieder aufgesteckt. Dadurch ist der rechtwinklige Umlenkhebel in Normallage wieder (geometrisch vorteilhaft) parallel zur Stoßstange beziehungsweise der Heckrotorwelle. Wie hier gezeigt, bedeutet das ein paar Grad positiven Anstellwinkel, um das normale Drehmoment des Hauptrotors auszugleichen, und gleichen Ausschlag von hier nach beiden Seiten.

Jetzt dreht der Heckrotor rechts herum (wie hier im Bild gesehen), die Heckrotorblätter laufen oben nach hinten, mit dem Hauptrotorabwind und nicht gegen ihn. So ist es beim Vorbild und so ist es auch (fast immer) "aerodynamisch" richtig.

Das Heckservo (hier: XServo X75 BLHV) wird vorne am Heckrohr angeklemmt – eine einfache und saubere Lösung. In der Anleitung und in Bildern habe ich mindestens vier verschiedene Möglichkeiten gesehen, wie herum man die Klemmstücke, die Befestigungsplatte und das Servo anbringen kann und wie gerade oder schräg das ganze auf das Heckrohr geklemmt wird. Dies war eine der Möglichkeiten und sie schien mir die eigentlich gemeinte zu sein (aber sicher bin ich nicht).

Das Heckrohr ist ganz dünnes Aluminium und sein vorderes Ende war beim Transport etwas eingebördelt. Es musste mit großer Kraft in die Fassung am Umlenkgetriebe gedreht und gedrückt werden – glücklicherweise wurde nichts anderes dabei verbogen.

Auch die Taumelscheibenservos (hier: XServo X70 BLHV) sind sehr gut angelenkt. Sie sitzen so in einem besonderen Rahmen, daß alle drei Anlenkstangen gleich lang sind. Die Längenangabe (96 mm) ist richtig, nur die mittlere Stange muß etwas kürzer sein, weil sie weniger schräg steht.

Auf YouTube wurde mehrfach gezeigt, daß man die mittlere Stange etwas kröpfen (im Bogen biegen) müsse, um eine Kollision mit dem mittleren Umlenkhebel zu vermeiden. Herr Illig hat in einem seiner Videos betont, daß es praktisch keine Kollision geben kann. Ich kann bestätigen, daß die mittlere Anlenkstange nicht gebogen werden muß.

Der mittlere Anlenkhebel ist übrigens dreieckig und hält den unteren Teil der Taumelscheibe gegen Verdrehen fest. Somit wird kein besonderer Halter benötigt.

Die Kugelgelenke bestehen aus einem recht harten Kunststoff und haben (deshalb?) ein klein wenig Spiel. Seltsam – bisher kannte ich nur Gelenke aus zähem Kunststoff und musste sie immer mit einer Flachzange etwas drücken, damit sie nicht zu stramm sitzen.

Für das Kreiselsystem (Flybarless-System) gibt es einen eigenen Platz, so daß es nahe bei den Servos installiert ist und genau parallel zur Hauptrotorebene liegt. Die Kabel sind gegen Scheuern an den Kanten der Ausschnitte geschützt, weil sie dort mit aufgeschnittenem Kraftstoffschlauch umhüllt sind.

Das Microbeast Plus HD wurde wegen der guten Erfahrungen mit dem Microbeast Plus in meiner HIROBO Schweizer 300 gewählt. Diese Version HD (heavy duty) hat eine zusätzliche MPX-Buchse als Hochstromanschluß, ratsam wegen der hier verwendeten Hochleistungsservos, die wiederum wegen der modernen Taumelscheibenanlenkung nötig sind. Die vier Hochvolt-Servos ziehen durchschnittlich ungefähr 5 A Strom, viel mehr als die in der HIROBO Schweizer 300. Zum Microbeast gehört sogar ein Schalter, den ich aber nicht benutze, weil ich (statt eines BEC) ohnehin den Schalter/Mischer (siehe unten) für zwei parallele Akkus habe, und die wiederum zur Sicherheit.

Einige Umstände hatte ich mit den Servoarmen: In der Anleitung wird empfohlen, solche aus Metall (Aluminium) zu nehmen. Ein zusätzliches Informationsblatt gibt an, daß für die neue Version der Taumelscheibenanlenkung die Servos mindestens 13 mm Hebelarm haben müssen. Später bestätigte sich, daß dies eine Mindestanforderung ist. Das Microbeast will wissen, wie viel Servoweg für genau 6° Pitch nötig ist, damit es nicht zu heftig reagiert. Mit 13 mm Servohebelarm reichte der maximal einstellbare Wert nur für 5,6° – das Microbeast ist auch mit diesem Wert zufrieden, aber der Hebelarm könnte etwas größer sein, mindestens 14 mm lang.

Passende Alu-Servoarme sind überhaupt schwer zu bekommen, mit 13 mm fand ich nur einen. Er passt aber nicht auf die Servowelle (nicht richtig entgratet, beim Eloxieren angeschwollen, aber auch Servowelle zu dick!) und hat ein Gewindeloch von 3 statt 2 mm Durchmesser. Später erfuhr ich vom Händler, daß XServo eine eigene Verzahnung der Servowelle hat, und es werden keine Alu-Servoarme dafür hergestellt – Mist! In einem Video von Scaleflying.de hieß es allgemein, daß Alu-Servoarme schwer zu bekommen sind, aber Kunststoffarme auch gehen. Also kamen die mitgelieferten Kunststoffarme auf die Servos – zunächst die mit 13 mm Hebelarm (Bild oben).

Die Mechanik bildet eine betriebsfähige Einheit. Frühere Versionen hatten sogar einen Vorbau für den Regler, daran zwei weitere Befestigungslaschen, aber davon ist man offensichtlich abgekommen. Jetzt müssen vier Laschen reichen und der Regler wird vor der Mechanik oben auf die Kabinendecke geschraubt.

Nach Fertigstellung der Mechanik wurde ein Probelauf mit den 12s-Antriebsakkus durchgeführt. Der Regler wurde als Drehzahlregler (governor) eingestellt und die Solldrehzahl eingelernt. Nach kurzem Einlaufen der Zahnräder und Lager lief der Antrieb ruhig und leicht. Der von der Telemetrie des Reglers gemessene Strom ist ein Maß für das Reibungsmoment und deutet darauf hin, daß der Gesamtwirkungsgrad des Haupt- und Heckrotorgetriebes ungefähr 94% beträgt.

Korrekturen

Aus mehreren Gründen ruhte der Weiterbau für längere Zeit. Dann bekam ich einen neuen Sender (PowerBox ATOM), das Microbeast bekam ein nützliches Update und alle Einstellungen wurden überprüft. Bei der Gelegenheit wurden auch die Pitchwinkel der vier Hauptrotorblätter (genauer: Blatthalter) angeglichen. Weil die Kugelgelenke immer nur um eine halbe Umdrehung verstellt werden können, blieb eine Differenz von maximal 0,2°.

Auch der Regler bekam ein nützliches Update und etwas veränderte Einstellungen. Während des anschließenden Probelaufs wurden die Solldrehzahlen neu justiert. Bei manchen Drehzahlen zeigten sich Schwingungen im Heckrotorantrieb. Das sah nach einem verrutschten Kugellager aus, konnte aber auch am großen Spiel im Antrieb liegen (in den beiden Kupplungen der Welle) und nach Montieren der Blätter verschwinden.

Zwischenzeitlich hatte mich ein freundlicher Heliflieger per E-Mail darauf hingewiesen, daß die Kupplungsstücke der Heckrotorwelle mit Linksgewinde an die Welle geschraubt sind. (Danke Roberto! Diese Information hatte ich mir von Scaleflying.de erhofft, aber nicht bekommen.) Die Teile können sich also lösen, wenn die Welle rechts herum läuft, wie in meinem Fall, weil ich das vordere Winkelgetriebe umgedreht habe. Was also tun?

Zuerst wurde das Winkelgetriebe am Heck angeschaut. Es läge nahe, das Abtriebs-Kegelrad von der rechten auf die linke Seite der Heckrotorwelle zu versetzen, um hier den Drehsinn des Heckrotors umzukehren. Dann hätte ich das Winkelgetriebe vorne wieder umdrehen können und die Welle würde links herum laufen. Leider ist das Getriebe hinten aber nicht symmetrisch aufgebaut, läßt sich also nicht umdrehen. Trotzdem wurde es auseinandergenommen, gereinigt, geölt und gefettet und wieder zusammengebaut. Jetzt läuft es leichter als vorher, wie das vordere auch. Übrigens waren (und sind) unter dem Abtriebskegelrad zwei Distanzscheiben, also war das Getriebe offenbar schon eingestellt.

In einem Forum hatte ich dann eine Diskussion über die ROBAN-Heckrotorgetriebe gefunden (August 2020, hier). Dort schrieb jemand, daß er die Kupplungsstücke auf der Welle gesichert hat, indem er quer durch das Gewinde bohrte und eine 2mm-Schraube einbaute. (Das empfiehlt Helikopter Baumann als ROBAN-Händler – hier.)

Mein Gedanke: Es könnte auch eine einfache Verstiftung reichen, das heißt 2 mm durchbohren und ein 8 mm langes Stück Stahldraht mit Loctite-Kleber einkleben. (So habe ich es an meiner HIROBO Schweizer 300 gemacht – hier.) Dann wurden die Löcher aber so groß, daß der Draht überhaupt nicht klemmte. Also wurde es doch eine Schraube mit einer nur schwach angezogenen, durch Loctite gesicherten Mutter.

Das Bohren der 2mm-Löcher war überraschenderweise nicht einfach. Ein leichter Schlag mit dem Körner muß genau auf dem Scheitel der Rundung sitzen, der Bohrer genau senkrecht dort ansetzen. Dazu ist Einspannen in einen Maschinenschraubstock wohl unerlässlich. Das Gewinde des Kupplungsstücks ist hohl, wie ich beim Bohren feststellte. Unten trifft der Bohrer auf eine so kleine Innenrundung, daß seine Spitze den Tiefpunkt nicht erreicht und seine Flanken seitlich einschneiden. Das lässt ihn auswandern und beide Löcher werden unrund und zu groß. Besser wäre gewesen, beide Löcher einzeln von außen zu bohren. Das bedeutet, exakt um 180° verdreht einzuspannen und zu körnen und jeweils nur bis in den Hohlraum zu bohren. Kritisch ist diese Sache aber offenbar nicht.

Die Welle aus dem Heckrohr ziehen ging überraschend leicht. Es stellte sich heraus, daß beide Kugellager fest auf der Welle verklebt sind, aber das vordere Gummistück war – offenbar wegen zu großer Reibung beim Einbau – halb vom Kugellager gerutscht. Das war also nicht richtig geführt und daher die Schwingungen. Leider ist das vordere Kugellager jetzt etwas schwergängig, vielleicht beim Einschieben beschädigt oder durch das Gleitmittel oder durch schräge Last vom verrutschten Gummistück. Mit etwas Wärme ließe sich das Lager lösen, aber wie soll ich an ein neues kommen? Das Lager läuft sich vielleich auch wieder ein und muß jetzt einfach noch gehen.

Die Welle wieder in das Heckrohr hineinschieben ging auch leicht, nachdem ich jetzt das Problem kannte und einen Trick fand: Die Gummistücke haben zwei "Lippen", die mit Spülmittel geschmiert werden. Das hatte ich beim ersten mal auch getan, aber dann die Welle in einem Zug ganz hineingeschoben. Das Schmiermittel war dabei nicht bis ganz nach vorne gekommen. Deshalb habe ich jetzt nur so weit geschoben, bis Widerstand zu spüren war, dann wieder etwas herausgezogen, bis wieder Schmierung zu spüren war, und so weiter hin und her bis die Welle ganz eingeschoben war.

Übrigens hat Scaleflying.de (im Video) wirklich dringend geraten, die beiden Lager ungleichmäßig auf der Welle im Heckrohr zu verteilen und dort festzukleben. Hingegen rät ROBAN (auf Seite 10 der Anleitung), die Lager gleichmäßig im Heckrohr zu verteilen (wie es andere Hersteller auch empfehlen). Ich habe keine Ahnung, welche Gründe Scaleflying.de hatte, aber sie müssen schon ihre Erfahrungen gemacht gehabt haben. Also bin ich (wieder) ihrem Rat gefolgt und nicht dem von ROBAN.

Also wurden die Kupplungsstücke gesichert und die Welle (richtig) wieder eingebaut. Das vordere Winkelgetriebe bleibt umgedreht, der Heckrotor dreht richtig herum, keine Schwingungen mehr (Probelauf) – und hoffentlich kein Aufdrehen eines Gewindes (auch nicht der Pitchhülse).

Nachdem die Mechanik und das Heck montiert waren, wurde noch einmal die Taumelscheibensteuerung überprüft. Bei extremen Ausschlägen von kollektiver und zyklischer Verstellung gab es zwar keine Kollisionen. Aber jetzt erst fiel mir auf, daß einzelne Servos dabei extreme Winkelausschläge hatten, die Servoarme mehr als 60° von der Neutrallage. Also sind die 13mm-Arme doch eher zu kurz und längere wären zumindest besser.

Quasi "auf den letzten Drücker" wurden sie durch 17mm-Arme (30% länger) ersetzt. Nun gab es Kollisionen der Servoarme, so daß einige überflüssige abgeschnitten werden mussten (am rechten und am mittleren Servo).

Wegen des größeren Schrägstands mussten die beiden äußeren Anlenkstangen um eine halbe Drehung einer Kugelgelenkhülse verlängert werden, damit die Taumelscheibe wieder waagerecht steht.

Im Kreiselsystem (Microbeast) mussten natürlich die Maximalausschläge deutlich reduziert werden, aber das war der Sinn der Sache, denn es macht die Ausschläge wieder annähernd linear. Der Nachteil der Sache ist, daß die Servos mehr Strom verbrauchen, weil sie mehr Kraft aufbringen müssen. 15mm-Arme wären in der Hinsicht besser. Jedenfalls bekommt das Microbeast jetzt seine vollen 6° Pitch schon bei kleineren Servowinkelausschlägen und kann damit angemessen auf Lageabweichungen reagieren. Am Heckrotorservo ist unverändert der 13mm-Arm, weil es hier keine zu großen Winkelausschläge gibt.

Rumpf

Die Landekufen sind durch die GFK-Hülle in eine Sperrholzstruktur gesteckt und innen verschraubt. Eigentlich gut gemacht, aber rechts hinten ging die runde Strebe nicht ganz hinein und hat letztlich etwas vom Kunststoff abplatzen lassen – aber nur unten, wo man es nicht sieht.

Weil man sie hier gut sieht: Scharniere und Griffe an den Türen sind nicht vorbildgerecht, aber nicht schlecht. Sie sind zwar etwas grob, fallen aber ebenso wenig auf wie die falsch angeklebten Trittstangen.

Mein Problem ist hier sichtbar: Die Trittstangen sind nur in der Mitte bündig eingeklebt, die "Ansätze" passen buchstäblich vorne und hinten nicht. Das Teil ist so steif, daß Spanngummis, Klebestreifen und nachher der Kleber nachgegeben haben. In die Spalte kommt jetzt noch großzügig Canopy Glue, der überbrückt sie etwas.

Hier sind sie von unten gesehen, aber nachher fallen sie kaum auf, siehe vorheriges Bild.

Die Türen sind schon fertig und recht hübsch. Die Inneneinrichtung, hauptsächlich Sitze, musste noch auf den mit beiger Farbe behandelten Sperrholz-Kabinenboden geklebt werden, mehr nicht. Sieht auch hübsch aus.

Man sieht etwas, daß unten an den Sitzgestellen Zungen sind, die in Schlitze im Boden gesteckt werden. Die Lage der Sitze in der Kabine ist also völlig klar; man kann sie praktisch nur dort festkleben.

Man sollte eine ganze Sitzreihe auf einmal festkleben, das heißt die zwei Gestelle pro Sitz in die Schlitze und die Sitze auf ihre jeweiligen Gestelle. Zuerst die Gestelle an die Sitze kleben wird nicht funktionieren, weil dafür alles zu ungenau ist. Canopy Glue läßt genügend Zeit zum Ausrichten der Sitzreihe.

Der Kasten in der Mitte hat eine Funktion: Er sitzt auf einem Schieber, der die Bodenplatte davor ver- und entriegelt. Man fasst an dem Kasten an, um den Schieber vor oder zurück zu bewegen. Funktioniert gut!

Auf der Bodenplatte sind drei Sitze, die man auch als Griff verwenden kann. Damit nimmt man die Platte samt Sitzen heraus und kommt so an das Akkufach.

In dem Abteil in der Mitte ist Platz für zwei 6s 5000mAh LiPo und and den Seiten für zwei Empfängerakkus. Dahinter (links im Bild) bleibt dann nur für das, was man sonst noch unterbringen will (Hauptschalter, Akkuweiche, Telemetriesensoren) sowie Kabel und Stecker.

Die Kabel nach oben zum Regler können durch den Schacht aus Sperrholz gezogen werden, der hinten im Bild (hinter der Ecke des Ausschnitts) zu erkennen ist. Vorne (rechts im Bild) sind die Pilotensitze, die im nächsten Bild von oben zu sehen sind.

Hier geht es aber um die Knüppel, also Steuerknüppel und Pitchhebel.

Im Original sitzt der Pilot rechts (links im Bild), aber er hat den Pitchhebel links von sich, nicht rechts wie hier. Der Sitz müsste im Modell weiter außen sein und der Pitchhebel zwischen Sitz und Mittelkonsole (aber das geht wegen der Zungen und Schlitze nicht ganz leicht). Rechts an der Mittelkonsole ist sogar noch eine Konsole (hier nicht sichtbar unter dem Panel). Das linke Bein beziehungsweise Knie des Piloten hat also nicht genug Platz.

Das hat der Konstrukteur des Modells wohl nicht richtig recherchiert, aber er hat sich andererseits große Mühe gegeben: Die Schalteraufsätze der Steuerknüppel sind spiegelbildlich verschieden, wie es bei dieser Anordnung hier nötig ist. Im Original sind natürlich beide Knüppel gleich, weil immer die rechte Hand am Steuerknüppel ist (und die linke am Pitchhebel).

Jedenfalls hätte ich den rechten Pilotensitz anders einbauen sollen. Es wäre möglich gewesen, für die beiden Steuerknüppel neue Löcher zu bohren. Die Zungen an den Sitzgestellen hätte man abschneiden und den Sitz einfach auf den Kabinenboden kleben können – an der richtigen Stelle. Und ich hätte die Sitzfläche tiefer machen können, so daß die Hände einer Pilotenpuppe an die Knüppelgriffe herankommen und der Helm nicht an die Kabinendecke stößt (siehe drei Bilder weiter).

Das Heck wird mit sechs Schrauben am Rumpf befestigt, wobei ein Schaumstoffteil auf dem Heckrohr wohl das Gewicht trägt. Den 2mm-Schrauben an dem Hebelarm würde ich das jedenfalls nicht zutrauen. Die Löcher kann beziehungsweise muß man – bei fixiertem Heck – buchstäblich freihändig bohren. Die Einschlagmuttern in Sperrholzstücken lagen bei. Weil man nachher sehr schlecht herankommt, wurden sie schon eingeklebt.

Die Frontscheibe ist angeschraubt. Zwei Scheibenwischerattrappen liegen dem Bausatz bei und die Bell 429 hat im Prinzip auch Wischer, nicht aber das Vorbild dieses Modells. Deshalb werden sie hier weggelassen.

Die zwei Antennen(attrappen) an der Triebwerkshaube sind angeklebt. Fünf weitere kommen zum Schluß, damit sie nicht bei den folgenden Arbeiten abgebrochen werden.

Die Abziehbilder sind aufgebracht – nach Anleitung im Video von Scaleflying.de. Und meine UAS-Betreiber-Nummer (e-ID) ist als QR-Code zwischen den Sternen vor dem schwarzen Abgasrohr versteckt.

Besonders ohne direktes Sonnenlicht kommt mir die rote Farbe des Rumpfes immer zu dunkel vor – verglichen mit dem Original und mit anderen Modellen. Vielleicht wurde eine Farbe verwendet, die je nach Beleuchtung verschieden aussieht, doch mir kommt dieser Rotton nicht ganz vorbildgerecht vor (aber er passt zum Teppich).

Ergänzung

Eine Pilotenpuppe im Maßstab 1:7 wurde auf den rechten Vordersitz gesetzt, wohin sie in der B 429 gehört. Sitz und Knüppel wurden nicht an die richtigen Stellen versetzt, weil sie zu fest am Kabinenboden kleben. Das linke Bein derPilotenpuppe geht gerade zwischen zyklischem Knüppel und der Konsole hindurch.

Die Figur sitzt fest auf dem Sitz und stößt mit dem Helm oben an der Decke an. Die Arme reichen nicht weit genug an die Knüppel heran, aber die Beine sind genau richtig lang für die Pedale. Also scheint eher der Sitz, genauer die Sitzfläche zu hoch zu sein.

Wenn man nicht sehr nahe heran geht fällt das alles nicht auf. Deshalb braucht es auch keine Gurte und überhaupt keine Befestigung. Im Flug sieht der Heli jetzt aber noch vorbildgerechter aus.

Heck

Weiter geht es mit dem Heck: hier helles Rot in direktem Sonnenlicht. In der Hecktüte befindet sich später das Rohr mit der Heckrotorwelle, deshalb kann das Höhenleitwerk nicht durchgesteckt werden. Statt dessen gibt es zwei Hälften, die in eingeformte Vertiefungen geklebt werden.

An den Enden sitzen noch Seitenleitwerke (geschraubt, aber auch geklebt) und auf denen sehr schöne, kleine Positionslampen (geklebt). Ich war mal wieder schusselig und habe die Seitenleitwerke verkehrt herum angebracht, aber das ist kein Problem und nur eine nicht vorbildgerechte Kleinigkeit mehr.

Hier liegt das Heck übrigens verkehrt herum, weil es so gerade ausgerichtet war, bis der Kleber getrocknet war. Es ist wieder Canopy Glue, weil er gut auf dem glatten Kunststoff haftet und weil er elastisch bleibt. Getrocknet fällt er später auch kaum auf.

Hinten an der Hecktüte wird später diese große Heckfinne mit Hecksporn und zwei Leuchten angeschraubt. Man sieht die Markierungen für vier Schraubenlöcher rund um den Kabelaustritt. Die Kabel gehören zu den Leuchten, die oben angeklebt werden. Der Hecksporn wird unten in ein Füllstück aus Holz eingeschraubt.

Das hübsche rote Warnlicht gehört zum Bausatz, aber kein weißes Positionslicht – wieder eine unerklärliche Abweichung von "Scale". Von einer Multiplex-Beleuchtung habe ich eine weiße LED aufgeklebt, wo beim Original das rückwärtige Positionslicht sitzt. Ein Loch für das Kabel bohren war kein Problem; das Ganze ist hohler Kunststoff.

Die große Heckfinne ist angeschraubt - man sieht einen schwarzen Schraubenkopf in der Öffnung. Sowohl in der Hecktüte als auch in der Finne waren je vier Vertiefungen für Schraubenlöcher. In der Hecktüte muss man den Kunststoff für die 3mm-Schrauben aufbohren. In der Finne – Kunststoff mit Holz innen als "Fleisch" – genügt 1mm oder 1,5mm, damit die Schrauben nicht zu fest gehen. (Die sind nämlich spröde und scheren leicht ab. Das betrifft alle Schrauben im Bausatz.)

Die Löcher in Tüte und Finne stimmten überein, also angeschraubt. Da wirkte die Finne aber arg nach vorne gekippt; im Vergleich mit dem Original war sie es auch. Also wieder abschrauben und mit dem Schaft des Bohrers (als Fräser) drei Löcher in der Hecktüte nach vorne und/oder oben erweitern (zu Langlöchern machen, eines davon im Bild sichtbar). Wieder anschrauben - jetzt ist es besser. Scheint ein Fehler in den Formen zu sein.

Es wäre besser gewesen, zuerst die Löcher in die Hecktüte zu bohren, dann die Finne in der richtigen Lage vorläufig zu befestigen, und dann die Löcher in der Finne durch die vorher gebohrten Löcher in der Hecktüte zu bohren. Die Hecktüte senkrecht (wie im Bild) und die Oberkante der Finne ebenfalls senkrecht könnte für die Ausrichtung passen, oder die Vorderkanten von zentraler Finne und Seitenfinnen parallel, oder die Oberkante waagerecht wie hier.

Im Bild sieht man die verkehrt herum angebrachten Seitenfinnen am Höhenleitwerk. Jetzt stimmen die Winkel der Vorderkanten nicht mit denen der zentralen Finne überein, aber das sieht man praktisch nicht. Der Hauptrotor liegt hoch genug, so daß er nicht kollidieren kann. (Und ich habe bei Scaleflying.de ein Bild von einer B 429 gesehen, an der die Finnen genauso falsch angebracht sind.)

Alle vier Leuchten sind fertig angeschlossen und getestet - sieht gut aus. Der mitgelieferte Controller für die Beleuchtung ist nicht schlecht. (Mittlerweile gibt es einen anderen.) Er hat noch drei freie Anschlüsse für Heckleuchten, von denen hier nur einer gebraucht wird. Und er lässt sich – mit einem Schalter am Sender – auf verschiedene Blinkmuster einstellen, auch auf das vorbildgerechte. (Das musste ich übrigens durch Ausprobieren selbst herausfinden.) Dabei blinkt nur das rote Warnlicht, und zwar so schön sanft, daß ich keinen anderen Controller nehmen mochte. Weil er nur bis zu 6V verträgt, musste ich sogar noch einen "Voltage Regulator" vorschalten, aber das war es mir wert.

Die Abziehbilder sind aufgebracht, wie man sieht. Und die sechs Löcher für die Befestigungsschrauben am vorderen Rand sind gebohrt (sieht man kaum).

Korrektur

Nach einer Weile kam eine gewisse Ernüchterung: Die Höhenleitwerke hielten nicht. Der von mir so geschätzte Canopy Glue hat sich gelöst, wo er doch eigentlich gerade auf Kunststoff sehr gut haftet. Vielleicht war er zu alt, oder auf den GFK-Teilen war noch Trennwachs, obwohl ich die Klebestellen mit Alkohol abgerieben hatte. Jedenfalls konnte ich den ganzen Klebstoff einfach abpulen und die Flächen wieder mit Alkohol säubern.

So hätte ich auch die Seitenleitwerke wieder ablösen und richtig herum ankleben können. Das scheiterte aber an den Positionsleuchten, die beim Ablösen zerstört worden wären. Es bleibt also bei den verkehrt angebrachten Seitenleitwerken.

Um die Haftung des Klebstoffs zu verbessern, wurden die Klebeflächen jetzt abgeschliffen und aufgerauht, zuerst (vor allem in den Ecken) mit einer kleinen Drahtbürste in einer Dremel-Maschine und dann noch mit Schleifpapier. Schließlich wurden sie wieder mit Alkohol abgerieben, was vielleicht auch die Oberfläche aktiviert.

Nun musste es also doch Epoxid sein. Eigentlich mag ich das Zeug nicht (und bekomme einen allergischen Schnupfen davon), aber es ging dann doch unerwartet gut. Eine gehörige Menge 30-Minuten-Epoxid wurde auf einem Stück Folie angerührt und mit einem Zahnstocher vor allem in die Ecken der Vertiefung in der Hecktüte verteilt. Diese Menge passte perfekt, denn als das Leitwerk von oben in die Vertiefung gedrückt wurde, floß das Epoxi hoch und bildete eine schöne Hohlkehle. Deshalb wurde das Leitwerk in senkrechter Lage mit Klebefilm an der Hecktüte fixiert und das Ganze zum Aushärten gelagert. Die andere Seite folgte dann entsprechend am nächsten Tag. Ein wenig Tempern mit einem Föhn hat das Aushärten beschleunigt, vielleicht sogar verbessert.

Jetzt sieht das Heck wieder so aus wie auf dem Bild oben, nur der Klebstoff ist klar-transparent und nicht milchig. Es scheint, daß er diesmal hält. Aber die Hecktüte ist als GFK-Teil in sich elastisch und die Leitwerke wippen bei Schwingungen etwas. Schlimmer noch, mit der Zeit hängen sie mehr und mehr herunter. Die Hecktüte ist einfach zu schwach.

Bei dieser Gelegenheit hätte ich noch Verstärkungen in die Hecktüte einbauen können und sollen, wie hier (in den Bildern unten auf der Seite, Bild 23 bis 25), aber jetzt ist es zu spät. Dort sind zwei Spangen innerhalb der Hecktüte miteinander verbunden (verklebt) und verbinden daher auch die beiden Leitwerke. Somit trägt die Hecktüte deren Gewicht, aber es gibt keine Biege- oder Torsionskräfte.

Als Provisorium spanne ich durchsichtiges Klebeband von einer Leitwerksspitze über die Hecktüte zur anderen (auf der Oberseite). Das ist praktisch eine dreieckige Verspannung. Die bleibt vor allem dran, wenn der Heli gelagert ist, um Materialermüdung zu vermeiden. Das Gleiche aus dünnem Draht wäre eine dauerhafte Lösung. Oder ein Streifen dickes Aluminiumblech, unten um die Hecktüte herumgebogen und flach an die Unterseite der Leitwerke geschraubt (sowie in passender Farbe lackiert). Sein Gewicht würde sogar helfen, den Schwerpunkt weiter nach hinten zu bringen.

Elektronik

Dieses Bild wird oben wegen der 17mm-Servoarme gezeigt, hier wegen der Verkabelung von Servos, Kreiselsystem (auf der Plattform dahinter) und Empfänger (daneben am Rumpf).

Die vier Servos sind ins Kreiselsystem eingesteckt, dann das Summensignal/Strom-Kabel vom/zum Empfänger und ein Kabel, um das Kreiselsystem mit einem USB-Adapter an einen PC anzuschließen. Dieses Kabel läuft in einem Bogen hinunter in den Boden des Helis. Damit kann man jederzeit Parameter einstellen. Schließlich läuft ein dickes schwarzes Kabel nach unten zu den "Empfängerakkus".

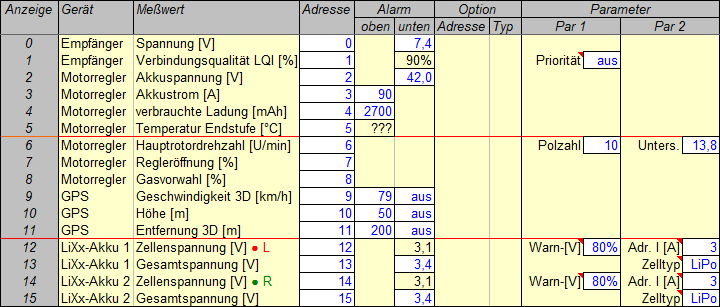

Das ist ein guter Platz für den Empfänger (Multiplex RX-12-DR compact M-Link), weil die Kabel vom Regler gerade bis hierhin reichen und die zwei Antennen gerade in die Attrappen der Abgasrohre. Das Kabel links gehört zum Regler, nach rechts gehen das Summensignal zum Kreiselsystem, der Telemetrie-Bus (Y-Kabel), die Lichter, der Antriebsakku-Sicherheitsschalter, die Aktivierung der Telemetriedatenaufzeichnung (nur eine Ader) und zwei schwarze Antennen.

Das schwarze Kabel, das spiralförmig in die Abgasrohr-Attrappe hineinläuft, ist die längere der beiden Empfänger-Antennen. Die kürzere läuft in die andere Abgasrohr-Attrappe. Beide Antennen sind in den Rohren einfach mit klarem Klebeband befestigt, wodurch sie ungefähr in 90° Winkel zueinander stehen.

Das GPS ist mit Klettband innen befestigt und über ein Y-kabel mit dem Telemetrie-Bus verbunden. An dieser Stelle hat es gute "Sicht" auf Satelliten und geringe elektronische Störungen.

Die Positionsdaten des GPS werden zur späteren Analyse aufgezeichnet für den Fall, daß einmal ein Mißgeschick geschieht. Ich lasse aber auch den Sender während des Fluges Geschwindigkeit, Höhe und Entfernung überwachen. Das GPS könnte sogar im Fall eines größeren Mißgeschicks nützlich sein: wenn der Heli in einem nicht einsehbaren Bereich (Kornfeld) verloren geht. Dann könnte man ihn finden, vorausgesetzt die Telemetrie arbeitet noch.

Der Motor KONTRONIK Pyro 700-45 (700er Größe, kv 450) sieht im Vergleich zum Hubschrauber klein aus, aber diese modernen hochwertigen Motoren sind einfach sehr leistungsfähig und ihre Leistung kommt zum Großteil von hoher Drehzahl (15.000 U/min), nicht nur von Drehmoment. Ein Lüfter zur Kühlung ist eingebaut.

Andererseits ist der Regler YGE Opto 135 (kein BEC, 135 A Dauer) ein wenig überdimensioniert, weil hier ein Regler für 12s LiPo gebraucht wird und ich einen Opto haben wollte, und da gab es den 135. (Ein YGE sollte es sein wegen der Multiplex-Telemetrie.) Dennoch ist der große Kühlkörper mit Lüfter angebracht, weil es unter der Haube nur die Luftschlitze vor dem Regler gibt.

Der Regler wurde so angeordnet, damit die Kabel geradewegs (nach rechts im Bild) in den senkrechten "Kabelkanal" hinunter unter den Kabinenboden zu den Akkus laufen können. Weil die Kabel trotzdem länger als 30 cm geworden sind, wurde noch ein Satz mit fünf Kondensatoren vor den Regler gelötet, um ihn vor Spannungsspitzen zu schützen – zur Sicherheit. Aber dann hätte ich den Regler auch nahe am Motor anbringen können, damit er mit seinem Gewicht nicht so weit vorne liegt. In dem Moment habe ich einfach nicht an den Schwerpunkt des Helis gedacht.

Die beiden dreiadrigen Kabel (Signal, Telemetrie) laufen geradewegs nach hinten zum Empfänger (rechts im Hintergrund) und ihre Länge passte gerade. Ich hätte sie nach unten unter den Kabinenboden ziehen sollen und von da mit Verlängerungen wieder hoch zum Empfänger. Dann könnte ich die Verbindung unten trennen und beide Kabel an den USB-Adapter zum PC anschließen, um Parameter zu verändern. Jetzt müsste ich dafür den Hauptrotor und die Haube abnehmen. Ich habe einfach befürchtet, daß die Kabel zu lang werden.

Die Abstände der Komponenten wirken geradezu optimal. Regler sowie Empfänger und Kreiselsystem haben voneinander den Maximalabstand – die Kabellänge. Der Motor liegt dazwischen, ist aber ohne Bürsten und damit auch ohne Bürstenfeuer. Wenn der Regler also direkt vor dem Motor liegen würde, gäbe es wahrscheinlich auch keine Störungen.

Übrigens sind hier zwei der vier Laschen aus Aluminium (mit schwarzen Schrauben und Unterlegscheiben) zu sehen, welche die Mechanik am Rumpf halten, rechts und links vom Motor. Eines der beiden unbenutzten Löcher mit Einschlagmuttern ist hinter den Kondensatoren sichtbar, zwischen den beiden Kabeln.

Bevor wir nun unten in die Kabine des Hubschraubers schauen, sollten wir noch festhalten, wie viel Platz doch unter der Haube dieser ROBAN Bell 429 ist; reichlich Platz (für den Regler) vor der Mechanik und ebenfalls dahinter in dem "Trichter" zur Hecktüte. In der ROBAN H145 (die ein Vereinskollege besitzt) geht es dort sehr beengt zu.

Im mittleren Fach unter dem Kabinenboden liegen die beiden 6s 5000 mAh 40C/80C LiPo Antriebsakkus mit XT90 Steckern. Sie sind in Reihe an den Sicherheitsschalter (EMCOTEC SPS SafetyPowerSwitch 70V 60/120A) angesteckt, der unten angeklettet ist. Er wird mit einem Schalter am Sender betätigt, durch einen am Empfänger angeschlossenen Adapter (SPS-Fernsteuerschaltgeber). Die grüne LED zeigt an, daß der Schalter an ist – der Antrieb ist aktiv.

Als ich nachträglich die Kondensatoren für den Regler hinzugefügt habe (vorheriges Bild), dachte ich nicht mehr daran, daß der SafetyPowerSwitch dann einen Parallelwiderstand braucht. Prompt war der Schalter beschädigt und ein neuer musste gekauft werden – und ein Widerstand (208-8 a 470R 10%). Jetzt ist die grüne LED immer an, wenn die Akkus angesteckt sind, auch wenn der Schalter aus ist. Also ist die LED nutzlos und mir macht es nichts mehr aus, daß der Adapter unsichtbar im Fach untergebracht ist. Wichtig ist nur, daß ich erst auf der Bahn den Antrieb scharfschalten kann und daß beim Anstecken der Akkus Blitzschutz besteht.

In jedem Seitenfach liegt (hier nicht sichtbar) ein 2s 2200 mAh 20C/40C LiPo "Empfängerakku" mit XT60 Stecker. Beide sind an den Schalter/Mischer (Jeti DSM10) angeschlossen, der weiter hinten verborgen ist. Er wird mit einem Magnetschalter aktiviert (nächstes Bild), was den konventionellen Schalter, der mit dem Microbeast HD Flybarless-System mitgeliefert wird, überflüssig macht. Diesen Schalter/Mischer habe ich gewählt, weil er kein Spannungsregler ist und ich deshalb die Akkuspannung (als Empfängerspannung) per Telemetrie überwachen kann.

An jeden Antriebsakku ist ein Spannungssensor angeschlossen. Sichtbar sind die weißen Balancer-Stecker, das rote Klettband auf den Sensoren und die dreiadrigen Kabel zum Sensorbus. Die Sensoren wurden später entfernt, weil zwei davon an in Reihe geschalteten Akkus nicht funktionieren können (anders als ich fälschlich angenommen hatte, siehe unten).

Das ist natürlich ein Durcheinander, aber es passt gerade in den Raum zwischen den Akkus und dem Spant rechts, falls die Akkus nach vorne geschoben sind. Alles wird dann durch den Deckel verdeckt, der Teil des Kabinenbodens ist und drei Sitze trägt (siehe oben). Keine Befestigung ist nötig, denn die Akkus kommen nicht aus, sie können sich nicht einmal im Fach bewegen. Also ist im Flug alles sicher – äußerst einfach. Wichtig ist hieran, daß der Schwerpunkt des Helis zu weit vorne liegt und die Akkus weiter hinten sein sollten – einfach unmöglich.

Der Schalter/Mischer für die Empfängerakkus wird mit einem Magnetschalter aktiviert. Ein Winkel aus Kunststoff wurde neben den linken Pilotensitz geklebt. Jetzt kann ich die Tür öffnen und den Magnet an den blauen Kreis halten, um ein- und auszuschalten. Die grüne LED zeigt an, daß die Empfängerakkus verbunden sind. Bei geschlossener Tür ist der Schalter nicht zu sehen.

Das runde Loch im Kabinenboden unter dem Sitz ist für die Schraube darunter, welche die vordere linke Strebe des Landegestells im Rumpf hält.

Das ist der FlightRecorder, das Aufzeichnungsgerät für Telemetriedaten. Es ist an die Rückseite des linken Pilotensitzes angeklettet. Es ist nicht sichtbar, wenn der Deckel mit den drei Sitzen eingesetzt ist, und sonst komme ich gut an die MicroSD-Karte heran.

Die grüne LED zeigt an, daß Daten aufgezeichnet werden. Hier ist das Gerät mit einem Servoausgang am Empfänger verbunden, um die Datenaufzeichnung ein- und auszuschalten. Das geschieht mit demselben Schalter am Sender, mit dem der Antriebs-Sicherheitsschalter betätigt wird.

Übrigens sieht man hier recht gut, was ich "Kabelkanal" nenne: auf der linken und der rechten Seite, von oberhalb der Kabinendecke bis unter den Kabinenboden, in das linke und das rechte Seitenfach.

Fertigstellung

Die Endmontage war nicht ganz einfach. Die Mechanik ist präzise gebaut, aber der Glasfaser-Rumpf mit der inneren Struktur aus Sperrholz und das Glasfaser-Heck haben größere Toleranzen, um nicht zu sagen sind ungenau gebaut. Das ist aber die Natur der Sache und heißt nur, daß wir uns darauf einstellen müssen. Alle Montageschritte müssen zunächst probeweise erfolgen und dabei umkehrbar sein.

Die Kabel müssen vorweg durch die Löcher in den Spanten gezogen werden, auch um zu sehen ob ihre Stecker durchgehen und ihre Länge passt. Die Mechanik mit den Befestigungslaschen muss im Rumpf so ausgerichtet werden, daß sowohl Heck als auch Haube passen. Die Löcher für die Schrauben, mit denen das Heck befestigt wird, könnten erst nach gemeinsamer Ausrichtung von Mechanik und Heck gebohrt werden. Das meiste davon gelang mir gut, es gab nur kleine Patzer.

Das ist der Zustand unmittelbar nach den letzten Montageschritten und es ist alles in Ordnung. Der Empfänger ist noch nicht eingebaut und ein paar Kabel hängen lose aus dem Rumpf heraus. Gut sichtbar ist, daß die Rotorwelle senkrecht steht, die Oberkante der Kabine aber geneigt ist. So steht der Hubschrauber am Boden, mit dem Heck waagerecht.

Nicht so gut sichtbar ist, daß die große Heckfinne noch nicht genug geneigt ist. Ihre Oberkante ist noch nicht ganz waagerecht und sie sollte es erst sein, wenn der Heli vorwärts fliegt und selbst waagerecht liegt. Ein weiterer Anhaltspunkt ist, daß die Vorderkante der großen Finne und die der kleinen Seitenfinne nicht parallel sind. Das ist ein kleiner Patzer (wie auch die verkehrt herum angebrachten Seitenfinnen).

Die Mechanik war probeweise in den Rumpf eingebaut worden, mit allen vier Befestigungslaschen und allen acht Schrauben. Dann war das Heck auf den Ausleger geschoben und schließlich die Heckrotoreinheit montiert worden. Dazu musste die Mechanik etwas nach hinten geschoben werden, denn sonst kommt man nicht durch die Öffnung hinten in der Hecktüte an die Schrauben heran. Die Heckrotoranlenkung ist auch schwer zugänglich. Das Heck wurde dann mit den vorgesehenen sechs kleinen Schrauben befestigt.

Die Mechanik war so ausgerichtet worden, daß der Heckausleger mittig in der Hecktüte verläuft und die Carbon-Rahmen mittig zwischen den längs laufenden Sperrholzwangen. Sie musste so weit wie möglich nach vorne (an einen Spant) geschoben werden, damit die Taumelscheibe gerade im Ausschnitt der Haube liegt. Jetzt erst wurden die acht Schrauben in den Befestigungslaschen handfest angezogen und die Laschen mit Canopy Glue fixiert.

Nachdem der abgebunden hatte, wurde alles wieder ausgebaut. Die vier Schrauben, die durch die Laschen in den Rahmen gehen, wurden nun mit Sicherungsmittel festgezogen. Die Komponenten wurden wie zuvor zusammengesetzt und ausgerichtet. Schließlich wurden auch die vier Schrauben, die durch die Laschen in die Einschlagmuttern in der Sperrholzstruktur gehen, mit Sicherungsmittel festgezogen. Unter allen acht Schrauben sind Unterlegscheiben, damit beim Festziehen die Laschen nicht verdreht oder verschoben werden.

Die Mechanik, genauer ihr unterer Teil mit dem Heckrotorgetriebe, muss an einem Sperrholzspant im Rumpf anliegen. Sie muß aber seitlich ein wenig nach rechts gedreht sein, um in die Hecktüte hineinzugehen. Es entsteht eine kleine Lücke zwischen der linken Rahmenseite und dem Spant, die im ersten Bild im Abschnitt Elektronik schwach zu sehen ist.

Die Taumelscheibe liegt aber weiter zurück im Ausschnitt der Haube, als diese Lücke breit ist. Das ist also ein "eingebauter" kleiner Patzer. Die hintere Taumelscheibenanlenkung ist gerade frei von der Haube und die "Zungen", welche die beiden anderen Anlenkungen berühren, wurden später abgefeilt.

Wieder der auffällig unterschiedliche Rotton, je nach Licht.

Das ist der fertige Hubschrauber in seiner ganzen Pracht, nur die Hauptrotorblätter fehlen (auf dem Flugplatz montiert, und die fehlenden fünf Antennen-Attrappen wurden nach dem Erstflug angeklebt). Keine offensichtlichen Ungenauigkeiten oder Patzer.

Diese Ansicht zeigt einen weiteren kleinen Patzer, den ich nicht rechtzeitig bemerkt hatte: Das Heck ist zur rechten Seite gedreht (in Flugrichtung gesehen). Das habe ich erst während der Probemontage bemerkt (als die Mechanik nicht ganz gerade hineinging), aber da war es schon zu spät zum korrigieren.

Sehr bald hatte ich die Hecktüte auf den "Hals" hinten am Rumpf gedrückt. Sie passte gut, ohne einen Spalt, also wurden die Löcher für die sechs Befestigungsschrauben gebohrt und die Einschlagmuttern eingeklebt. Das war leicht. Ich hätte auch auf die Ausrichtung der Mechanik achten und einen kleinen Spalt auf der rechten Seite in Kauf nehmen können. Es wäre aber schwer gewesen, die Hecktüte in richtiger Ausrichtung zu fixieren, und sie würde nicht so gut am Rumpf sitzen. Wie die Dinge jetzt sind ist mir ganz recht.

Und noch etwas, das man – wenn überhaupt – hier sieht: Der Heckrotor ist etwas nach rechts gedreht (von hinten gesehen, nach links wie hier gesehen). Das fiel mir schon auf, als ich die Mechanik montiert hatte, und ich dachte an einen Montagefehler. Aber es muß so gewollt sein, denn im Heckrohr ist vorne ein Ausschnitt und hinten eine Loch, über welche die Lage vorgegeben ist. Im Flug ist der Hubschrauber nach links geneigt, dann steht der Heckrotor genau senkrecht – so passt es wieder, denke ich mir einfach.

Zwischen den Blattspitzen und dem Höhenleitwerk sind 8 mm Abstand – genügend. Wenn die Mechanik nicht nach rechts gedreht wäre, dann wäre sie 2 mm weiter vorne und der Abstand wäre 6 mm – immer noch genügend.

Der rechtwinklige Umlenkhebel für die Blattverstellung ist hier in Normallage, das heißt parallel zur Stoßstange beziehungsweise der Heckrotorwelle. Das bedeutet ein paar Grad positiven Anstellwinkel der Heckrotorblätter, um das normale Drehmoment des Hauptrotors auszugleichen.

Wegen der schrägen Blattspitzen ist das schwer zu erkennen. Der Rotorkreisdurchmesser ist 290 mm an der Blattvorderkante gemessen und 300 mm an der Blatthinterkante. Zumindest der Drehsinn des Heckrotors ist gut zu erkennen.

Die große Heckfinne sieht gut aus, aber sie scheint immer noch nicht weit genug nach hinten geneigt zu sein. Ein wenig mehr wäre besser gewesen, aber das war kaum sichtbar, als das Heck noch nicht an den Rumpf montiert war.

Übrigens ist der Heckrotor ein weiteres Detail, das nicht ganz "scale" ist. Das Vorbild hat einen eigenartigen Heckrotor, eigentlich zwei zweiblättrige hintereinander auf der Heckrotorwelle und um 55° gegeneinander verdreht (sogenannter Scheren-Heckrotor für mehr Wirkung und weniger Lärm), also nicht vier Blätter in einer Ebene und um 90° gegeneinander verdreht wie hier. Außerdem sitzt die Heckrotorwelle des Originals höher, fast oben auf der Hecktüte, und ist um 6,1° nach hinten gedreht. Aber schlicht und einfach so wie hier gefällt mir sogar besser.

Alle Rotorblätter waren vorweg ausgewuchtet worden. Da Haupt- und Heckrotor je vier Blätter haben, wurden jeweils die beiden leichtesten und die beiden schwersten (mit der Blattwaage) ermittelt. Die Paare wurden mit farbigem Klebeband markiert (rot-grün und gelb-blau) und mit den beigefügten weißen Klebestreifen am Ende des jeweils leichteren Blattes ausgewogen. Man liest oft, daß die ROBAN-Blätter sehr ungleich sein sollen, aber hier war nicht viel Ausgleich nötig – vielleicht weil paarweise ausgewogen werden kann. Die Blatthalter wurden so mit entsprechendem farbigem Klebeband markiert, daß die Blätter jeweils paarweise gegenüber liegen. So kommt jedes Blatt immer wieder an denselben Halter und eine eventuelle individuelle Einstellung des Blattwinkels bleibt erhalten. (Die Anlenkungen der Blatthalter an der Taumelscheibe bleiben mit den Blatthaltern verschraubt, so daß sie keine farbigen Markierungen brauchen.)

Die meisten farbigen Markierungen innerhalb der Blatthalter sieht man hier. Vor allem sieht man die winkelförmigen Taumelscheibenanlenkungen, die einen Taumelscheibenmitnehmer überflüssig machen.

Sie sind auf jeden Fall eine gute Sache und geschickt gestaltet, aber sie sehen doch ein wenig schwach aus im Vergleich zu denen an 3D-Helis. Sie scheinen ein wenig elastisch, nicht ganz steif zu sein.

Jedenfalls hatte ich Mühe, den Blattspurlauf einzustellen. In etlichen Messrunden mit der Pitchlehre waren die Messungen nicht ganz reproduzierbar. Erst nach einigem Probieren und Einstellen zeigten drei weitere Messrunden eine ausreichende Übereinstimmung der Blattwinkel.

Schließlich sieht man, wie der Ausschnitt in der Haube rechts und links mit einer Feile vergrößert (begradigt) wurde, damit die Taumelscheibenanlenkungen nicht anstoßen.

Schaut man noch einmal auf die Blatthalter, dann kann man sich vorstellen, wie die beiden hinteren Blätter um 45° nach hinten gedreht werden können und die beiden vorderen um 45° nach vorne.

Auf diese Weise verstaue ich die Hauptrotorblätter für Transport und Lagerung des Hubschraubers, mit zwei auf die Blattspitzen geschobenen geschlitzten Stücken aus dickem elastischen Schaumstoff. Das hintere Stück hält den ganzen Rotor gerade über dem Rumpf.

Der blaue Schaumstoff wurde mit Schere und Messer zugeschnitten, deshalb sehen die Stücke etwas roh aus. Das hätte man natürlich schöner machen können. Davon abgesehen kann man die Blätter auch anders verstauen, nämlich je eines gerade nach vorne und hinten sowie die beiden anderen um 90° nach hinten gedreht, wie hier gezeigt (drittes Bild). Jedenfalls ist die Länge von der vorderen Blattspitze bis zur Spitze des Hecksporns ungefähr 1,90 m.

Einstellungen

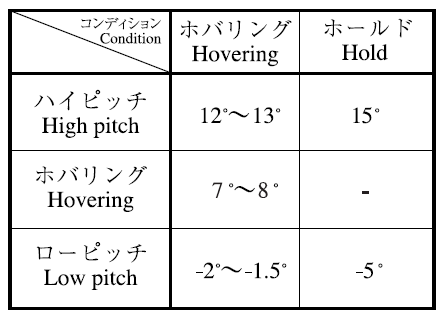

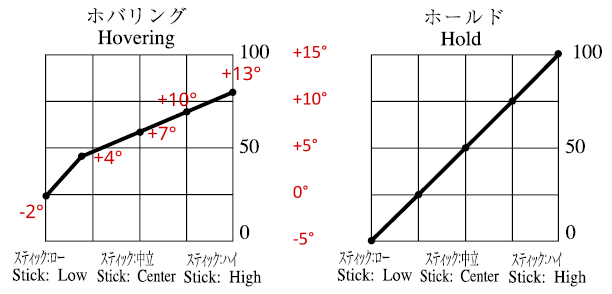

Nachdem die Taumelscheibe und die Heckrotoranlenkung richtig eingestellt waren, fehlten nur noch entsprechende Einstellungen im Kreiselsystem (Flybarless-System) und im Sender. Die Anleitung von ROBAN gibt nur eine konkrete Empfehlung: Der kollektive Blattwinkel sollte zwischen -2/-3° und +9/+10° liegen und linear sein. Das schien mir ein wenig dürftig, also griff ich – mangels eigener Erfahrung – auf die Anleitung für den Dreiblattrotor der HIROBO S-300 zurück. Die folgenden zwei Bilder stammen daher. Nach meinem Verständnis sollte sie auch hier anwendbar sein, weil beide Hubschrauber ein gewölbtes Hauptrotor-Blattprofil haben.

Mit "Hold" ist Autorotation gemeint, also habe ich diesen weiten Bereich

von -5° bis +15° als absolute Grenzen im Microbeast Flybarless-System

eingestellt (was dann -100% bis +100% im Sender sind). Die langen Servoarme

würden noch größere (übermäßige) Ausschläge

erlauben.

Das mag jetzt immer noch übermäßig erscheinen, aber im Notfall (Heckrotorausfall) könnte es nötig sein. Wenn ein zyklischer Blattwinkel zu einem schon großen kollektiven hinzukommen muss, dann sollte das Kreiselsystem beim Mischen von beiden diese absoluten Grenzen einhalten.

Die 15° Blattwinkel machen mir keine Sorgen, weil gewölbte Profile höhere Anstellwinkel erreichen als symmetrische und am Drehflügel noch höhere – und weil der Anstellwinkel wegen des Rotorabwinds deutlich kleiner ist als der Blattwinkel.

Die Anleitung von ROBAN erwähnt, daß schwere Scale-Hubschrauber (wie dieser) sehr schwer in Autorotation sicher zu landen sind, besonders aus dem Schwebeflug. Wir werden das also nicht unnötig tun, müssen es aber, wenn der Heckrotor ausfällt. (Hoffentlich nicht, aber trotzdem übe ich im Simulator.) Meine Multiplex-Sender haben alle schon einen besonderen, vorrangigen Flugmodus für Autorotation, in dem der maximale (100%) positive und negative Blattwinkel möglich ist. In allen anderen Flugphasen (wie Multiplex das nennt) ist der Blattwinkel von vorneherein etwas begrenzt.

In meinem neuen Sender PowerBox ATOM ist nichts dergleichen vorbereitet, also habe ich es dort anhand der Tabelle oben und der Diagramme unten (beide von HIROBO) nachvollzogen. Nach der Spalte "Hovering" in der Tabelle soll der Blattwinkel zwischen -2° bis -1.5° und +12° bis +13° liegen, und nach dem linken Diagramm soll die Pitch-Kurve aus zwei Geradenstücken bestehen. Das bedeutet (1) der Pitch-Knüppel ist beim Schwebeflug ungefähr in der Mitte, (2) die Pitch-Kurve ist in dem Bereich relativ flach und lässt feinfühliges Steuern zu, und (3) wir nehmen für kleine Blattwinkel eine steile Kurve in Kauf, brauchen sie aber nur am Boden. Weil der ATOM keine speziellen Hubschrauber-Kurven hat, nur allgemein Kurven für Knüppelausschläge, müsste die schwarze Skalierung der Diagramme eigentlich -100/0/+100 (statt 0/50/100) sein. Die rote Blattwinkel-Skalierung zwischen den beiden Diagrammen habe ich hinzugefügt, ebenso wie im linken Diagramm die von mir wirklich auf der 5-Punkt-Kurve eingestellten Winkel für meine drei "normalen" Flugphasen. Meine Kurve ist ein wenig steiler als die im Diagramm, um mehr maximalen Blattwinkel für den Notfall zu haben (den Wirbelringzustand, der dann auch bald kam).

Diese Pitch-Kurven für "normale" Flugphasen (links) und

für Autorotation (rechts) sind so verschieden, daß ein weicher,

langsamer Übergang (vielleicht 1 oder 2 Sekunden)

eingestellt werden sollte.

Es gibt keine Empfehlungen für den Heckrotor-Blattwinkel, weder von ROBAN noch von HIROBO. I habe die Anlenkung so eingestellt, daß bei Servo in Mittelstellung der rechtwinklige Umlenkhebel im Heck sowohl zum Heckrohr als auch zur Heckrotorwelle parallel ist. Das ergibt ungefähr 6° "Mittel"-Blattwinkel. Dann habe ich einfach +/-9° nach jeder Seite im Microbest Kreiselsystem eingestellt. Die Kreiselempfindlichkeit für das Heck wurde auf den empfohlenen Standardwert eingestellt, was genau gepasst hat.

Die Blattwinkel an Haupt- und Heckrotor bei verschiedenen Drehzahlen wurden im Simulator überprüft. Wenn jemand ein schwereres Modell oder einen anderen Motor hat oder mit anderen Drehzahlen fliegt, könnte er das durchaus ebenfalls tun (siehe unten).

Im Sender sind drei kombinierte Ausschlagraten (100%, 80% und 60%) und Expo-Werte (50%, 40% und 30%) an einem Dreifachschalter eingerichtet. Sie sind unabhängig von den Flugphasen und gelten für zyklischen Blattwinkel und Heckrotor-Blattwinkel. Die Kombinationen ergeben ungefähr die gleiche Expo-Kurve um die Knüppel-Mitte herum, also unabhägig von der Rate. Eigentlich benutze ich nur die kleinste Rate.

Die Anleitung von ROBAN betont, daß Scale-Hubschrauber große Massenträgheit besitzen und deshalb im Flybarless-System eine geringere Kreiselempfindlichkeit eingestellt werden muß als für 3D-Hubschrauber. Das erreicht man mit einer speziellen Einstellung im Microbeast Kreiselsystem, die für einen ausgewählten "Charakter" des Helis (hier "scale" oder ähnliches) einige Parameter automatisch einstellt.

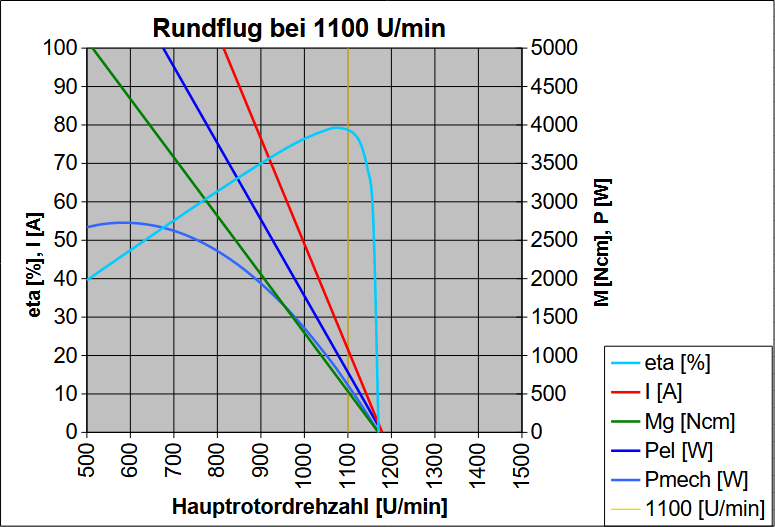

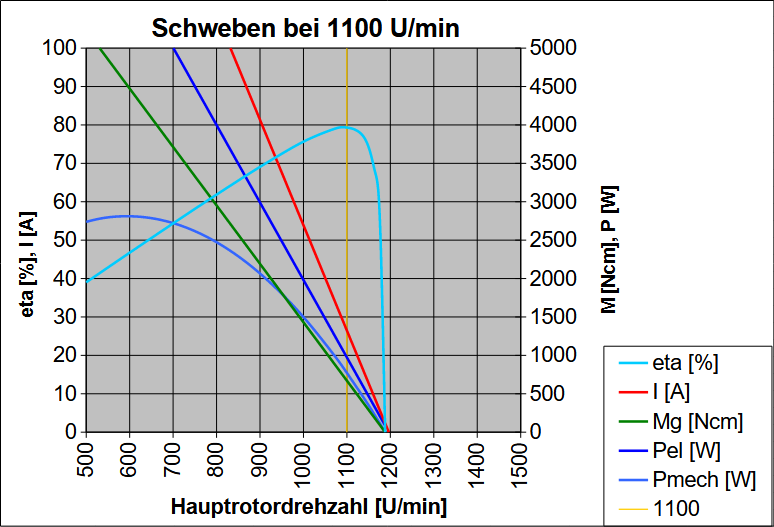

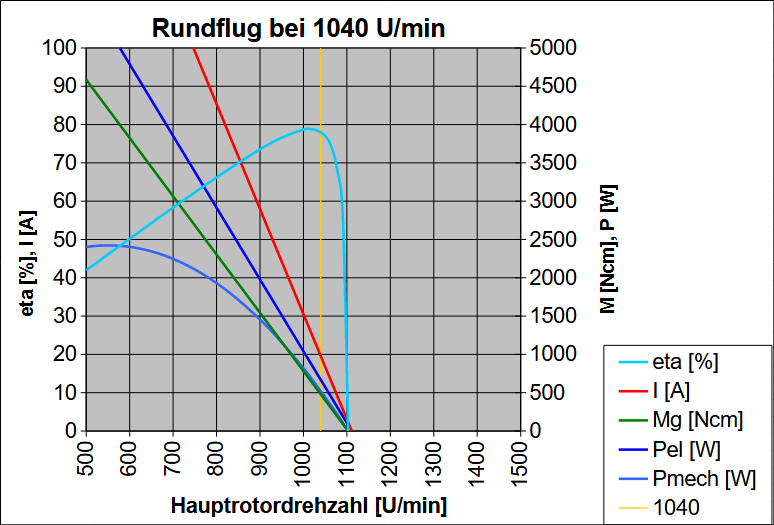

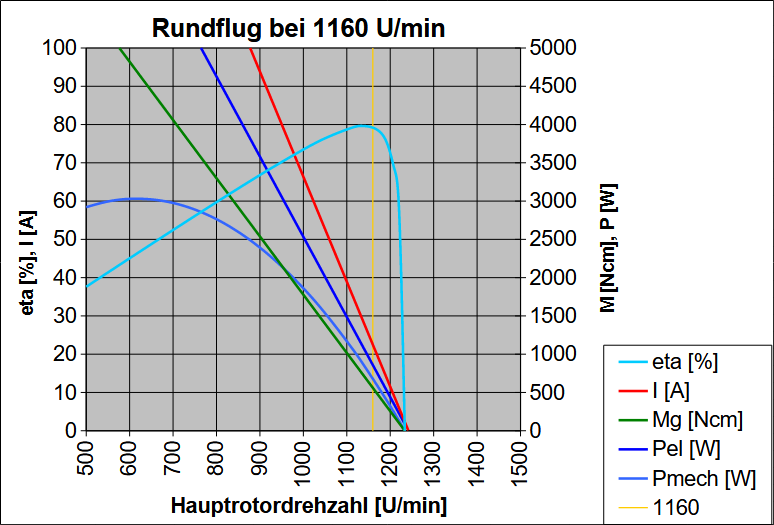

Drei "normale" Flugphasen (nicht Autorotation) sind eingerichtet, um im Flug zwischen verschiedenen Hauptrotordrehzahlen umzuschalten: 1040 U/min (sparsam), 1100 U/min (normal) und 1160 U/min (böiger Wind). Dafür wurden diagonale "Gaskurven" mit 33 Punkten verwendet, die oben auf die jeweilige Solldrehzahl begrenzt sind (die der Governor dann umsetzt). Der "Gas"-Kanal ist einem Drehknopf am Sender zugeordnet, so daß ich immer noch von Hand einen langsamen Hochlauf steuern kann (ungefähr wie mit einem Limiter in früheren Sendern). Sonst wird der Übergang von einer Drehzahl zur anderen vom Sender verlangsamt (Übergangszeit zwischen Flugphasen) als auch vom Regler (langsamer Hochlauf).

Die Flugphase Autorotation könnte eigentlich die Soll-Rotordrehzahl ("Gaskurve") ganz auf Null heruntersetzen, aber sie wird (nach der Anleitung zum Regler von YGE) nur auf etwas unter 20% des Maximalwertes gesetzt. Das soll einen unmittelbaren Wiederhochlauf des Motors ermöglichen, wenn man zum Testen oder Üben die Autorotation eingeschaltet hat und sie wieder beenden will. Der Regler (Governor) geht nämlich in den langsamen Hochlauf, wenn Null gesetzt wurde, und das würde zu lange dauern. Andererseits könnte ein schneller Hochlauf von weniger als 10% bis 20% der Maximaldrehzahl den Motor überlasten.

Fliegen

Das folgende Bild zeigt den Hubschrauber nach dem Erstflug am 29. September 2024. Die Heckrotorblätter stehen hier in die falsche Richtung gedreht, weil das Kreiselsystem reagiert hat, als ich den Heli beim Tragen gedreht habe. Der Schatten auf dem Heck stammt von unserer Birke und zeigt wieder, daß die rote Farbe in Sonnenlicht viel heller aussieht als sonst. Man sieht auch, daß im Innenraum des Helis alles "scale" ist. Bei den 700 und 800 Modellen von ROBAN ist dort eben keine Mechanik wie bei den kleineren 600ern. Umso mehr wird zumindest eine Pilotenpuppe gebraucht (und später wurde eine hinzugefügt). Das Geräusch des Helis gefällt mir gut, ein Soundmodul brauche ich nicht.

Ein oder zwei Hauptrotorblätter liefen noch nicht in der Spur, aber das wurde vor dem zweiten Flug behoben. Sonst gab es nichts zu bemängeln, außer vielleicht, daß beim Hochlauf zeitweise die Höhenleitwerke in Resonanz mit irgendwelchen Schwingungen kamen und auf und ab vibrierten. Eine nachträgliche Abhilfe ist schwer vorstellbar (vielleicht dünne Verspannungen).

Der Heli fliegt sehr ruhig und stabil, aber auch sehr agil. Das Flybarless-System (Microbeast) ist ganz nach den Empfehlungen des Herstellers eingestellt und die passen offensichtlich hervorragend. Dazu gehört, die maximal möglichen Taumelscheibenausschläge anzugeben. (Deshalb wurden noch die Servoarme gewechselt.) Diese Ausschläge sind im normalen Betrieb bei weitem übertrieben. Am Sender sind drei Möglichkeiten mit 100%, 80% und 60% Rate sowie 50%, 40% und 30% Expo per Schalter wählbar. Ich fliege bisher nur mit der kleinsten Rate und werde wohl noch geringere ausprobieren (und mehr Expo). All das gilt auch für den Heckrotor.

Nur sollte man vor dem Fliegen etwas beachten: Das Microbeast Flybarless-System braucht unmittelbar nach dem Einschalten absolute Ruhe, das heißt nicht die kleinste Erschütterung. Der Heli sollte möglichst waagerecht stehen. Erst wenn dann nach einer Weile die Taumelscheibe auf und ab bewegt wird, hat das System sich kalibriert und der virtuelle Horizont stimmt. Und nachdem der Heli zum Startpunkt getragen und dort abgestellt wurde, stelle ich noch die Heckrotorblätter in Normalstellung (ungefähr 6°). Dann gelingt der Start ohne Kippeln und Wackeln. (Vermutlich ist das bei allen Flybarless-Systemen so, aber ich habe nur zwei Microbeasts.)

Der Schwerpunkt des Helis liegt ein ganzes Stück vor der Rotorwelle. Offensichtlich gleicht das Kreiselsystem das "stillschweigend" aus, das heißt es hält den Heli automatisch waagerecht. (Gut daß der Hauptrotor vier Blätter hat und nicht nur zwei.) Also werde ich wohl keinen Ballast ins Heck tun, auch nicht, wenn Pilotenpuppen vorne hineinkommen.

Die Flugleistung des 8,8 kg schweren Helis (7 kg ohne Akkus) reicht für "Scale" sicher aus – der 700er Motor an 12s 5000 mAh LiPo, die 1100 U/min des 1,60m-Hauptrotors, die vier Blätter mit S-Schlag-Profil. Und die Leistung des Heckrotors reicht sicher aus, den Heli in Seitenwind auf der Stelle zu halten und um seitwärts zu fliegen. (Und die Leistung reicht immer noch sicher aus bei nur 1040 U/min des Hauptrotors.) Das folgende Video zeigt die ersten zwei Minuten des zweiten Fluges am 6. Oktober 2024 und mehr meine "eckige" Flugweise als das Verhalten des Helis. An die Steigleistung und die Agilität dieses Hubschraubers muß ich mich erst noch gewöhnen (und auch noch an meinen neuen Sender).

Die aufgezeichneten Telemetriedaten zeigen, daß – im Durchschnit – im Schwebeflug etwas mehr als 25 A Strom gezogen werden, im Rundflug etwas mehr als 20 A. Im Durchschnitt wird hier betont, weil der Strom stark schwankt – zwischen 10 A und 40 A. Nur in heftigen Flugbewegungen steigt er über 40 A und nur einmal (als ich in Panik voll Pitch gegeben habe) gab es eine Spitze von 87 A. (Das kann durch Begrenzung des Kollektiv-Pitch-Ausschlags im Sender verhindert werden.) Der mit 135 A belastbare Regler (YGE) ist also für normalen Flug überdimensioniert. Er wird aber trotz oder wegen dieser niedrigen Teillast (15% bis 20% vom Grenzwert) nur bis zu 50°C warm (wahrscheinlich durch den "aktiven Freilauf").

Der Verbrauch beträgt durchschnittlich ungefähr 360 mAh/min (entspricht 21,6 A). Nach 7 Minuten Flugzeit (einschließlich Hochlauf) beträgt die Zellenspannung der beiden 6s-Akkus (5000 mAh) noch 3,8 V (Lagerspannung). Die beiden 2s-"Empfängerakkus" (2200 mAh) verlieren bis zu 0,1 V Zellenspannung pro Flug, also sind sie gut für drei oder vier solche Flüge. Ohne Gefahr für alle Akkus könnte man Flüge zu je 8 Minuten Dauer machen, mit den "Empfängerakkus" vier hintereinander, müsste sie am Ende aber wieder auf Lagerspannung aufladen.

Der Verbrauch beträgt nur 325 mAh/min (entspricht 19,6 A) bei nur 1040 U/min Hauptrotordrehzahl – ohne irgendeinen merklichen Verlust an Leistung und Agilität. Eine noch kleinere Hauptrotordrehzahl (und weniger Strom) ist möglich. Man könnte Flüge zu je 8 Minuten Dauer machen, mit den "Empfängerakkus" jetzt aber nur drei hintereinander, und hätte am Ende immer noch ungefähr Lagerspannung.

Übrigens kann man jetzt den durchschnittlichen Servostrom schätzen. Vier 7-Minuten-Flüge machen ungefähr eine halbe Stunde, 3,8 V Leerlaufzellenspannung bedeutet – sehr grob gerechnet – halbe Entladung der beiden parallelen 2200 mAh "Empfängerakkus". Diese sind also mit 1C Strom belastet, das sind 4,4 A. Großzügig aufgerundet sind das 5 A als Größenordnung (genauer gerechnet sogar 5,4 A, und immer noch knapp 5 A mit 15mm-Armen an den Taumelscheibenservos). Der Servostrom ist im Schwebeflug deutlich geringer als im Rundflug (siehe geringeren Spannungsabfall am Ende des Beispieldiagramms unten).

Der Hubschrauber fliegt sich sehr angenehm, aber es gibt ein paar Dinge zu beachten: Ich bin noch in der Lern- und Gewöhnungsphase und in einem Fall bekam ich einen Schrecken, als der Heli im Schwebeflug plötzlich durchsackte. Voller Pitch-Ausschlag ließ ihn zwar wieder hochschießen, aber ich fühlte mich an einen Rat aus der Anleitung erinnert – den Heli immer in Bewegung zu halten, außer in Bodennähe (im Bodeneffekt). Es könnte eine Neigung zum Wirbelringzustand geben.

Und ich mag die Form, das Farbschema und die Farbe des Hubschraubers sehr, aber gerade die können schlechte Sichtbarkeit verursachen. Das Farbschema hat überhaupt keine klaren geraden Linien und nicht einmal die Landekufen sind parallel. Bei bedecktem Himmel sieht der Rumpf dunkel aus, der Kontrast ist gering. Die abgerundete Form wiederum hat einen Umriss, der es manchmal schwer macht, die Fluglage des Helis zu erkennen und die Orientierung zu behalten. Jedenfalls fliege ich den Heli bei Sonnenschein entspannter als bei Bewölkung. Dieser Heli ist sehr schön, aber nichts für Anfänger. Man kann nicht alles haben.

Zum Schluß zwei Kommentare: Einer auf YouTube nennt den Heli eine Schönheit – einverstanden. Der Enkel eines Vereinskollegen nennt ihn einen Weihnachtshubschrauber – nicht einverstanden, aber verstanden (und unwissentlich liegt er nicht ganz falsch, siehe oben).

Fazit

… im Telegrammstil:

- Schönes, vorbildgetreues Modell.

- Unwesentliche Details sind nicht "scale".

- Diese können beim Bau (aber nicht danach) korrigiert werden.

- Solide aufgebaut, gute Qualität, guter Preis.

- Gut gestaltete Mechanik.

- Heckrotor kann auf rechtsdrehend geändert werden.

- Bei Autorotation dreht der Heckrotor mit.

- Fliegt ruhig aber ist doch agil.

- Nicht für Anfänger – Erfahrung hilft.

- Aber auch nicht besonders schwierig.

Für – auch einige schwierige – Details siehe vorherige Abschnitte.

Die wichtigsten Informationen sind in den folgenden Anmerkungen zusammengefasst, wichtige Details siehe oben.

Anmerkungen

Ein Motor der Größe 700 mit kv 450 ist gerade richtig für diesen Heli. Ein größerer Motor (750 oder 800) hätte nur eine übermäßige Leistungsreserve, einer mit mehr kv (520 oder 560) würde mehr Strom ziehen und sogar den Regler belasten. Nur wenn man billige Komponenten (Motor, Regler, Akku) mit hohem Innenwiderstand verwendet, sollte es eher ein Motor der Größe 750 sein, um eine gute Leistungsreserve zu haben.

Der Motor sollte nicht viel mehr als 50 mm Außendurchmesser haben (wahrscheinlich höchstens ungefähr 60 mm) um in die Ausbuchtung im Rahmen zu passen. Es muß in jedem Fall eine Ausführung mit langem Wellenstummel sein: 38,5 mm oder nur etwas länger (und 6 mm Durchmesser).

Ein Regler, der mindestens 100 A Strom verträgt, ist auf der sicheren Seite. Er sollte aber in jedem Fall teillastfest sein ("aktiver Freilauf").

Zwei 6s LiPo-Akkus mit 5000 mAh Kapazität genügen dann für 8 Minuten Flugzeit (solange sie neu sind), kleinere Akkus (4000 mAh) sind also möglich. Der mittlere Strom ist 20 A bis 22 A; Spitzen gehen bis 40 A, nur in extremen Fällen bis 90 A.

Wegen der recht langen Kabel vom Regler zu den Akkus sind zusätzliche Kondensatoren ratsam. Ein Sicherheitsschalter dürfte dann einen Parallelwiderstand brauchen.

Gute Heli-Servos in Standardgröße (für mindestens 600er Helis) sind nötig. In Hochvolt-Ausführung werden sie aus einem 2s LiPo-Akku gemeinsam mehr als 5 A Strom ziehen (im Durchschnitt). Ein Flybarless-System mit Hochstromanschluß oder eine eigene Servostromversorgung ist ratsam.

13 mm Servohebelarm ist eine Mindestanforderung, sollte aber besser 14 mm lauten. 17 mm Hebelarm funktioniert sehr gut, aber mit 15mm-Armen könnten die Servos 10% weniger Strom ziehen.

Servoarme aus Aluminium sind gut, aber es gibt sie nicht für alle Servo-Marken. Servoarme aus Kunststoff tun es zur Not auch.